Randomized Algorithms (Spring 2010)/Balls and bins

Today's materiels are the common senses in the area of randomized algorithms.

Probability Basics

In probability theory class we have learned the basic concepts of events and random variables. The following are some examples:

event [math]\displaystyle{ \mathcal{E} }[/math]: random variable [math]\displaystyle{ X }[/math]: [math]\displaystyle{ \mathcal{E}_1 }[/math]: 75 out of 100 coin flips are HEADs [math]\displaystyle{ X_1 }[/math] is the number of HEADs in 100 coin flips [math]\displaystyle{ \mathcal{E}_2 }[/math]: the outcome of rolling a 6-sided die is an even number (2, 4, 6) [math]\displaystyle{ X_2 }[/math] is the result of rolling a die [math]\displaystyle{ \mathcal{E}_3 }[/math]: tomorrow is rainy [math]\displaystyle{ X_3=1 }[/math] if tomorrow is rainy and [math]\displaystyle{ X_3=0 }[/math] if otherwise

There are natural ways of transforming between random variables and events.

- An event can be defined out of a random variable [math]\displaystyle{ X }[/math] by a predicate [math]\displaystyle{ P(X) }[/math]. ([math]\displaystyle{ \mathcal{E} }[/math]: X>2)

- A boolean random variable [math]\displaystyle{ X }[/math] can be defined out of an event [math]\displaystyle{ \mathcal{E} }[/math] as follows:

- [math]\displaystyle{ X=1 }[/math] if event [math]\displaystyle{ \mathcal{E} }[/math] occurs and [math]\displaystyle{ X=0 }[/math] if otherwise. We say that [math]\displaystyle{ X }[/math] indicates the event [math]\displaystyle{ \mathcal{E} }[/math]. We will later see that this indicator trick is very useful for probabilistic analysis.

The formal definitions of events and random variables are related to the foundation of probability theory, which is not the topic of this class. Here we only give some informal descriptions of what is what (you may ignore them if they confise you):

- A probability space is a set [math]\displaystyle{ \Omega }[/math] of elementary events, also called samples. (6 sides of a die)

- An event is a subset of [math]\displaystyle{ \Omega }[/math], i.e. a set of elementary events. ([math]\displaystyle{ \mathcal{E}_2 }[/math]: side 2, 4, 6 of the die)

- A random variable is not really a variable, but a function! The function maps events to values. ([math]\displaystyle{ X_2 }[/math] maps the first side of the die to 1, the second side to 2, the third side to 3, ...)

The axiom foundation of probability theory is laid by Kolmogorov, one of the greatest mathematician of the 20th century, who advanced various very different fields of mathematics.

Independent events

Definition (Independent events):

|

This definition can be generalized to any number of events:

Definition (Independent events):

|

Note that in probability theory, the word "mutually independent" is not equivalent with "pair-wise independent", which we will learn in the future.

The union bound

We are familiar with the principle of inclusion-exclusion for finite sets.

Principle of Inclusion-Exclusion:

|

The principle can be generalized to probability events.

Principle of Inclusion-Exclusion:

|

The proof of the principle is due to measure theory, and is omitted here. The following inequality is implied (nontrivially) by the principle of inclusion-exclusion:

Theorem (the union bound):

|

The name of this inequality is Boole's inequality. It is usually referred by its nickname "the union bound". The bound holds for arbitrary events, even if they are dependent. Due to this generality, the union bound is one of the most useful probability inequalities for randomized algorithm analysis.

Linearity of expectation

Let [math]\displaystyle{ X }[/math] be a discrete random variable. The expectation of [math]\displaystyle{ X }[/math] is defined as follows.

Definition (Expectation):

|

Perhaps the most useful property of expectation is its linearity.

Theorem (Linearity of Expectations):

|

Proof: By the definition of the expectations, it is easy to verify that (try to prove by yourself): for any discrete random variables [math]\displaystyle{ X }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ Y }[/math], and any real constant [math]\displaystyle{ c }[/math],

- [math]\displaystyle{ \mathbf{E}[X+Y]=\mathbf{E}[X]+\mathbf{E}[Y] }[/math];

- [math]\displaystyle{ \mathbf{E}[cX]=c\mathbf{E}[X] }[/math].

The theorem follows by induction. [math]\displaystyle{ \square }[/math]

Example:

|

The real power of the linearity of expectations is that it does not require the random variables to be independent, thus can be applied to any set of random variables. For example:

- [math]\displaystyle{ \mathbf{E}\left[\alpha X+\beta X^2+\gamma X^3\right] = \alpha\cdot\mathbf{E}[X]+\beta\cdot\mathbf{E}\left[X^2\right]+\gamma\cdot\mathbf{E}\left[X^3\right]. }[/math]

However, do not exaggerate this power!

- For an arbitrary function [math]\displaystyle{ f }[/math] (not necessarily linear), the equation [math]\displaystyle{ \mathbf{E}[f(X)]=f(\mathbf{E}[X]) }[/math] does not hold generally.

- For variances, the equation [math]\displaystyle{ var(X+Y)=var(X)+var(Y) }[/math] does not hold without further assumption of the independence of [math]\displaystyle{ X }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ Y }[/math].

Balls-into-bins model

Imagine that [math]\displaystyle{ m }[/math] balls are thrown into [math]\displaystyle{ n }[/math] bins, in such a way that each ball is thrown into a bin which is uniformly and independently chosen from all [math]\displaystyle{ n }[/math] bins.

There are several interesting questions we could ask about this random process. For example:

- the probability that there is no bin with more than one balls (the birthday problem)

- the probability that there is no empty bin (coupon collector problem)

- the expected number of balls in each bin (occupancy problem)

- the maximum load of all bins with high probability (occupancy problem)

Birthday paradox

There are [math]\displaystyle{ m }[/math] students in the class. Assume that for each student, his/her birthday is uniformly and independently distributed over the 365 days in a years. We wonder what the probability that no two students share a birthday.

Due to the pigeonhole principle, it is obvious that for [math]\displaystyle{ m\gt 365 }[/math], there must be two students with the same birthday. Surprisingly, for any [math]\displaystyle{ m\gt 57 }[/math] this event occurs with more than 99% probability. This is called the birthday paradox. Despite the name, the birthday paradox is not a real paradox.

We can model this problem as a balls-into-bins problem. [math]\displaystyle{ m }[/math] different balls (students) are uniformly and independently thrown into 365 bins (days). More generally, let [math]\displaystyle{ n }[/math] be the number of bins. We ask for the probability of the following event [math]\displaystyle{ \mathcal{E} }[/math]

| [math]\displaystyle{ \mathcal{E} }[/math]: there is no bin with more than one balls (i.e. no two students share birthday). |

We first analyze this by counting. There are totally [math]\displaystyle{ n^m }[/math] ways of assigning [math]\displaystyle{ m }[/math] balls to [math]\displaystyle{ n }[/math] bins. The number of assignments that no two balls share a bin is [math]\displaystyle{ {n\choose m}m! }[/math].

Thus the probability is given by:

- [math]\displaystyle{ \begin{align} \Pr[\mathcal{E}] = \frac{{n\choose m}m!}{n^m}. \end{align} }[/math]

Recall that [math]\displaystyle{ {n\choose m}=\frac{n!}{(n-m)!m!} }[/math]. Then

- [math]\displaystyle{ \begin{align} \Pr[\mathcal{E}] = \frac{{n\choose m}m!}{n^m} = \frac{n!}{n^m(n-m)!} = \frac{n}{n}\cdot\frac{n-1}{n}\cdot\frac{n-2}{n}\cdots\frac{n-(m-1)}{n} = \prod_{k=1}^{m-1}\left(1-\frac{k}{n}\right). \end{align} }[/math]

There is also a more "probabilistic" argument for the above equation. To be rigorous, we need the following theorem, which holds generally and is very useful for computing the AND of many events.

By the definition of conditional probability, [math]\displaystyle{ \Pr[A\mid B]=\frac{\Pr[A\wedge B]}{\Pr[B]} }[/math]. Thus, [math]\displaystyle{ \Pr[A\wedge B] =\Pr[B]\cdot\Pr[A\mid B] }[/math]. This hints us that we can compute the probability of the AND of events by conditional probabilities. Formally, we have the following theorem: Theorem:

- Let [math]\displaystyle{ \mathcal{E}_1, \mathcal{E}_2, \ldots, \mathcal{E}_n }[/math] be any [math]\displaystyle{ n }[/math] events. Then

- [math]\displaystyle{ \begin{align} \Pr\left[\bigwedge_{i=1}^n\mathcal{E}_i\right] &= \prod_{k=1}^n\Pr\left[\mathcal{E}_k \mid \bigwedge_{i\lt k}\mathcal{E}_i\right]. \end{align} }[/math]

Proof: It holds that [math]\displaystyle{ \Pr[A\wedge B] =\Pr[B]\cdot\Pr[A\mid B] }[/math]. Thus, let [math]\displaystyle{ A=\mathcal{E}_n }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ B=\mathcal{E}_1\wedge\mathcal{E}_2\wedge\cdots\wedge\mathcal{E}_{n-1} }[/math], then

- [math]\displaystyle{ \begin{align} \Pr[\mathcal{E}_1\wedge\mathcal{E}_2\wedge\cdots\wedge\mathcal{E}_n] &= \Pr[\mathcal{E}_1\wedge\mathcal{E}_2\wedge\cdots\wedge\mathcal{E}_{n-1}]\cdot\Pr\left[\mathcal{E}_n\mid \bigwedge_{i\lt n}\mathcal{E}_i\right]. \end{align} }[/math]

Recursively applying this equation to [math]\displaystyle{ \Pr[\mathcal{E}_1\wedge\mathcal{E}_2\wedge\cdots\wedge\mathcal{E}_{n-1}] }[/math] until there is only [math]\displaystyle{ \mathcal{E}_1 }[/math] left, the theorem is proved. [math]\displaystyle{ \square }[/math]

- Let [math]\displaystyle{ \mathcal{E}_1, \mathcal{E}_2, \ldots, \mathcal{E}_n }[/math] be any [math]\displaystyle{ n }[/math] events. Then

Now we are back to the probabilistic analysis of the birthday problem, with a general setting of [math]\displaystyle{ m }[/math] students and [math]\displaystyle{ n }[/math] possible birthdays (imagine that we live in a planet where a year has [math]\displaystyle{ n }[/math] days).

The first student has a birthday (of course!). The probability that the second student has a different birthday is [math]\displaystyle{ \left(1-\frac{1}{n}\right) }[/math]. Given that the first two students have different birthdays, the probability that the third student has a different birthday from the first two is [math]\displaystyle{ \left(1-\frac{2}{n}\right) }[/math]. Continuing this on, assuming that the first [math]\displaystyle{ k-1 }[/math] students all have different birthdays, the probability that the [math]\displaystyle{ k }[/math]th student has a different birthday than the first [math]\displaystyle{ k-1 }[/math], is given by [math]\displaystyle{ \left(1-\frac{k-1}{n}\right) }[/math]. So the probability that all [math]\displaystyle{ m }[/math] students have different birthdays is the product of all these conditional probabilities:

- [math]\displaystyle{ \begin{align} \Pr[\mathcal{E}]=\left(1-\frac{1}{n}\right)\cdot \left(1-\frac{2}{n}\right)\cdots \left(1-\frac{m-1}{n}\right) &= \prod_{k=1}^{m-1}\left(1-\frac{k}{n}\right), \end{align} }[/math]

which is the same as what we got by the counting argument.

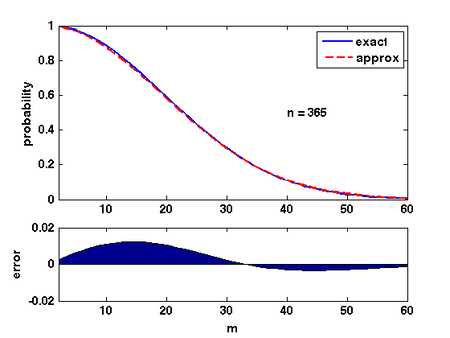

There are several ways of analyzing this formular. Here is a convenient one: Due to Taylor's expansion, [math]\displaystyle{ e^{-k/n}\approx 1-k/n }[/math]. Then

- [math]\displaystyle{ \begin{align} \prod_{k=1}^{m-1}\left(1-\frac{k}{n}\right) &\approx \prod_{k=1}^{m-1}e^{-\frac{k}{n}}\\ &= \exp\left(-\sum_{k=1}^{m-1}\frac{k}{n}\right)\\ &= e^{-m(m-1)/2n}\\ &\approx e^{-m^2/2n}. \end{align} }[/math]

The quality of this approximation is shown in the Figure.

Therefore, for [math]\displaystyle{ m=\sqrt{2n\ln \frac{1}{\epsilon}} }[/math], the probability that [math]\displaystyle{ \Pr[\mathcal{E}]\approx\epsilon }[/math].

Coupon collector's problem

Suppose that a chocolate company releases [math]\displaystyle{ n }[/math] different types of coupons. Each box of chocolates contains one coupon with a uniformly random type. Once you have collected all [math]\displaystyle{ n }[/math] types of coupons, you will get a prize. So how many boxes of chocolates you are expected to buy to win the prize?

The coupon collector problem can be described in the balls-into-bins model as follows. We keep throwing balls one-by-one into [math]\displaystyle{ n }[/math] bins (coupons), such that each ball is thrown into a bin uniformly and independently at random. Each ball corresponds to a box of chocolate, and each bin corresponds to a type of coupon. Thus, the number of boxes bought to collect [math]\displaystyle{ n }[/math] coupons is just the number of balls thrown until none of the [math]\displaystyle{ n }[/math] bins is empty.

| Theorem: Let [math]\displaystyle{ X }[/math] be the number of balls thrown uniformly and independently to [math]\displaystyle{ n }[/math] bins until no bin is empty. Then [math]\displaystyle{ \mathbf{E}[X]=nH(n) }[/math], where [math]\displaystyle{ H(n) }[/math] is the [math]\displaystyle{ n }[/math]th harmonic number. |

Proof: Let [math]\displaystyle{ X_i }[/math] be the number of balls thrown while there are exactly [math]\displaystyle{ i-1 }[/math] nonempty bins, then clearly [math]\displaystyle{ \sum_{i=1}^n X_i }[/math].

When there are exactly [math]\displaystyle{ i-1 }[/math] nonempty bins, throwing a ball, the probability that the number of nonempty bins increases (i.e. the ball is thrown to an empty bin) is

- [math]\displaystyle{ p_i=1-\frac{i-1}{n}. }[/math]

[math]\displaystyle{ X_i }[/math] count the number of balls thrown to make the number of nonempty bins increases from [math]\displaystyle{ i-1 }[/math] to [math]\displaystyle{ i }[/math]. Thus, [math]\displaystyle{ X_i }[/math] follows the geometric distribution, such that

- [math]\displaystyle{ \Pr[X_i=k]=(1-p_i)^{k-1}p_i }[/math]

For a geometric random variable, [math]\displaystyle{ \mathbf{E}[X_i]=\frac{1}{p_i}=\frac{n}{n-i+1} }[/math].

Let me help you remember what geometric distribution is and how we compute its expectation. - Bernoulli trial (Bernoulli distribution)

- Bernoulli trial describes the probability distribution of one coin flipping. Suppose that we flip a (biased) coin whose probability of HEADS is [math]\displaystyle{ p }[/math]. Let [math]\displaystyle{ X }[/math] be the 0-1 random variable which indicates whether the result is HEADS. We say that [math]\displaystyle{ X }[/math] follows the Bernoulli distribution with parameter [math]\displaystyle{ p }[/math]. Formally, [math]\displaystyle{ \Pr[X=1]=p }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ \Pr[X=0]=1-p }[/math].

- Geometric distribution

- Suppose we flip the same coin repeatedly until HEADS appears, where each coin flipping is independent and follows the Bernoulli distribution with parameter [math]\displaystyle{ p }[/math]. Let [math]\displaystyle{ X }[/math] be the random variable denoting the total number of coin flips. Then [math]\displaystyle{ X }[/math] has the geometric distribution with parameter [math]\displaystyle{ p }[/math]. Formally, [math]\displaystyle{ \Pr[X=k]=(1-p)^{k-1}p }[/math].

- For geometric [math]\displaystyle{ X }[/math], [math]\displaystyle{ \mathbf{E}[X]=\frac{1}{p} }[/math]. This can be verified by directly computing [math]\displaystyle{ \mathbf{E}[X] }[/math] by the definition of expectations. There is also a smarter way to compute [math]\displaystyle{ \mathbf{E}[X] }[/math] by indicators. For [math]\displaystyle{ k=0, 1, 2, \ldots }[/math], let [math]\displaystyle{ Y_k }[/math] be the 0-1 random variable such that [math]\displaystyle{ Y_k=1 }[/math] if and only if none of the first [math]\displaystyle{ k }[/math] coin flipings are HEADS, thus [math]\displaystyle{ \mathbf{E}[Y_k]=\Pr[Y_k=1]=(1-p)^{k} }[/math]. A key observation is that [math]\displaystyle{ X=\sum_{k=0}^\infty Y_k }[/math]. Thus, due to the linearity of expectations,

- [math]\displaystyle{ \begin{align} \mathbf{E}[X] = \mathbf{E}\left[\sum_{k=0}^\infty Y_k\right] = \sum_{k=0}^\infty \mathbf{E}[Y_k] = \sum_{k=0}^\infty (1-p)^k = \frac{1}{1-(1-p)} =\frac{1}{p}. \end{align} }[/math]

Back to our analysis of the coupon collector's problem, applying the linearity of expectations,

- [math]\displaystyle{ \begin{align} \mathbf{E}[X] &= \mathbf{E}\left[\sum_{i=1}^nX_i\right]\\ &= \sum_{i=1}^n\mathbf{E}\left[X_i\right]\\ &= \sum_{i=1}^n\frac{n}{n-i+1}\\ &= n\sum_{i=1}^n\frac{1}{i}\\ &= nH(n), \end{align} }[/math]

where [math]\displaystyle{ H(n) }[/math] is the [math]\displaystyle{ n }[/math]th Harmonic number, and [math]\displaystyle{ H(n)=\ln n+O(1) }[/math]. Thus, for the coupon collectors problem, the expected number of coupons required to obtain all [math]\displaystyle{ n }[/math] types of coupons is [math]\displaystyle{ n\ln n+O(n) }[/math].

[math]\displaystyle{ \square }[/math]

Only knowing the expectation is not good enough. We would like to know how fast the probability decrease as a random variable deviates from its mean value.

| Theorem: Let [math]\displaystyle{ X }[/math] be the number of balls thrown uniformly and independently to [math]\displaystyle{ n }[/math] bins until no bin is empty. Then [math]\displaystyle{ \Pr[X\ge n\ln n+cn]\lt e^{-c} }[/math] for any [math]\displaystyle{ c\gt 0 }[/math]. |

Proof: For any particular bin [math]\displaystyle{ i }[/math], the probability that bin [math]\displaystyle{ i }[/math] is empty after throwing [math]\displaystyle{ n\ln n+cn }[/math] balls is

- [math]\displaystyle{ \left(1-\frac{1}{n}\right)^{n\ln n+cn} \lt e^{-(\ln n+c)} =\frac{1}{ne^c}. }[/math]

By the union bound, the probability that there exists an empty bin after throwing [math]\displaystyle{ n\ln n+cn }[/math] balls is

- [math]\displaystyle{ \Pr[X\ge n\ln n+cn] \lt n\cdot \frac{1}{ne^c} =e^{-c}. }[/math]

[math]\displaystyle{ \square }[/math]

Occupancy problems

Now we ask about the loads of bins. Assuming that [math]\displaystyle{ m }[/math] balls are uniformly and independently assigned to [math]\displaystyle{ n }[/math] bins, for [math]\displaystyle{ 1\le i\le n }[/math], let [math]\displaystyle{ X_i }[/math] be the load of the [math]\displaystyle{ i }[/math]th bin, i.e. the number of balls in the [math]\displaystyle{ i }[/math]th bin.

An easy analysis shows that for every bin [math]\displaystyle{ i }[/math], the expected load [math]\displaystyle{ \mathbf{E}[X_i] }[/math] is equal to the average load [math]\displaystyle{ m/n }[/math].

Because there are totally [math]\displaystyle{ m }[/math] balls, it is always true that [math]\displaystyle{ \sum_{i=1}^n X_i=m }[/math].

Therefore, due to the linearity of expectations,

- [math]\displaystyle{ \begin{align} \sum_{i=1}^n\mathbf{E}[X_i] &= \mathbf{E}\left[\sum_{i=1}^n X_i\right] = \mathbf{E}\left[m\right] =m. \end{align} }[/math]

Because for each ball, the bin to which the ball is assigned is uniformly and independently chosen, the distributions of the loads of bins are identical. Thus [math]\displaystyle{ \mathbf{E}[X_i] }[/math] is the same for each [math]\displaystyle{ i }[/math]. Combining with the above equation, it holds that for every [math]\displaystyle{ 1\le i\le m }[/math], [math]\displaystyle{ \mathbf{E}[X_i]=\frac{m}{n} }[/math]. So the average is indeed the average!

Next we analyze the distribution of the maximum load. We show that when [math]\displaystyle{ m=n }[/math], i.e. [math]\displaystyle{ n }[/math] balls are uniformly and independently thrown into [math]\displaystyle{ n }[/math] bins, the maximum load is [math]\displaystyle{ O\left(\frac{\log n}{\log\log n}\right) }[/math] with high probability.

Theorem: Suppose that [math]\displaystyle{ n }[/math] balls are thrown independently and uniformly at random into [math]\displaystyle{ n }[/math] bins. For [math]\displaystyle{ 1\le i\le n }[/math], let [math]\displaystyle{ X_i }[/math] be the random variable denoting the number of balls in the [math]\displaystyle{ i }[/math]th bin. Then

|

Proof: Let [math]\displaystyle{ M }[/math] be an integer. Take bin 1. For any particular [math]\displaystyle{ M }[/math] balls, these [math]\displaystyle{ M }[/math] balls are all thrown to bin 1 with probability [math]\displaystyle{ (1/n)^M }[/math], and there are totally [math]\displaystyle{ {n\choose M} }[/math] distinct sets of [math]\displaystyle{ M }[/math] balls. Therefore, applying the union bound,

- [math]\displaystyle{ \begin{align}\Pr\left[X_1\ge M\right] &\le {n\choose M}\left(\frac{1}{n}\right)^M\\ &= \frac{n!}{M!(n-M)!n^M}\\ &= \frac{1}{M!}\cdot\frac{n(n-1)(n-2)\cdots(n-M+1)}{n^M}\\ &= \frac{1}{M!}\cdot \prod_{i=0}^{M-1}\left(1-\frac{i}{n}\right)\\ &\le \frac{1}{M!}. \end{align} }[/math]

According to Stirling's approximation, [math]\displaystyle{ M!\approx \sqrt{2\pi M}\left(\frac{M}{e}\right)^M }[/math], thus

- [math]\displaystyle{ \frac{1}{M!}\le\left(\frac{e}{M}\right)^M. }[/math]

Due to the symmetry. All [math]\displaystyle{ X_i }[/math] have the same distribution. Apply the union bound again,

- [math]\displaystyle{ \begin{align} \Pr\left[\max_{1\le i\le n}X_i\ge M\right] &= \Pr\left[(X_1\ge M) \vee (X_2\ge M) \vee\cdots\vee (X_n\ge M)\right]\\ &\le n\Pr[X_1\ge M]\\ &\le n\left(\frac{e}{M}\right)^M. \end{align} }[/math]

When [math]\displaystyle{ M=3\ln n/\ln\ln n }[/math],

- [math]\displaystyle{ \begin{align} \left(\frac{e}{M}\right)^M &= \left(\frac{e\ln\ln n}{3\ln n}\right)^{3\ln n/\ln\ln n}\\ &\lt \left(\frac{\ln\ln n}{\ln n}\right)^{3\ln n/\ln\ln n}\\ &= e^{3(\ln\ln\ln n-\ln\ln n)\ln n/\ln\ln n}\\ &\le e^{-3\ln n+3(\ln\ln n)(\ln n)/\ln\ln n}\\ &\le e^{-2\ln n}\\ &= \frac{1}{n^2}. \end{align} }[/math]

Therefore,

- [math]\displaystyle{ \begin{align} \Pr\left[\max_{1\le i\le n}X_i\ge \frac{3\ln n}{\ln\ln n}\right] &\le n\left(\frac{e}{M}\right)^M &\lt \frac{1}{n}. \end{align} }[/math]

[math]\displaystyle{ \square }[/math]

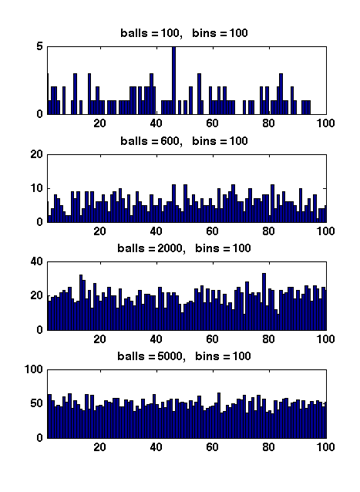

When [math]\displaystyle{ m\gt n }[/math], Figure 1 illustrates the results of several random experiments, which show that the distribution of the loads of bins becomes more even as the number of balls grows larger than the number of bins.

Formally, it can be proved that for [math]\displaystyle{ m=\Omega(n\log n) }[/math], with high probability, the maximum load is within [math]\displaystyle{ O\left(\frac{m}{n}\right) }[/math], which is asymptotically equal to the average load.

Tail inequalities

As shown by the example of occupancy problem, when applying probabilistic analysis, we often want a bound in form of [math]\displaystyle{ \Pr[X\ge t]\lt \epsilon }[/math] for some random variable [math]\displaystyle{ X }[/math] (think that [math]\displaystyle{ X }[/math] is a cost such as running time of a randomized algorithm). We call this a tail bound, or a tail inequality.

In principle, we can bound [math]\displaystyle{ \Pr[X\ge t] }[/math] by directly estimating the probability of the event that [math]\displaystyle{ X\ge t }[/math] (like we did to the coupon collector's problem and the occupancy problem). Besides this ad hoc analysis, we also would like to have some general tools which may give estimations of tail probabilities based on certain information regarding the random variables.

Markov's inequality

One of the most natural information about a random variable is its expectation. Markov's inequality gives a tail bound using only the information of expectation.

Theorem (Markov's Inequality):

|

Proof: Let [math]\displaystyle{ Y }[/math] be the indicator such that

- [math]\displaystyle{ \begin{align} Y &= \begin{cases} 1 & \mbox{if }X\ge t,\\ 0 & \mbox{otherwise.} \end{cases} \end{align} }[/math]

It holds that [math]\displaystyle{ Y\le\frac{X}{t} }[/math]. Since [math]\displaystyle{ Y }[/math] is 0-1 valued, [math]\displaystyle{ \mathbf{E}[Y]=\Pr[Y=1]=\Pr[X\ge t] }[/math]. Therefore,

- [math]\displaystyle{ \Pr[X\ge t] = \mathbf{E}[Y] \le \mathbf{E}\left[\frac{X}{t}\right] =\frac{\mathbf{E}[X]}{t}. }[/math]

[math]\displaystyle{ \square }[/math]

Chebyshev's inequality

Markov's inequality is the best we can get if all we know about the random variable is its expectation. Additional information about a random variable is expressed in terms of its moments.

Definition (moments):

|

Given the first and the second moments, the variance of the ramdom variable can be computed.

Definition (variance):

|

With the information of the expectation and variance of a random variable, one can derive a stronger tail bound known as Chebyshev's Inequality.

Theorem (Chebyshev's Inequality):

|

Proof: Observe that

- [math]\displaystyle{ \Pr[|X-\mathbf{E}[X]| \ge t] = \Pr[(X-\mathbf{E}[X])^2 \ge t^2]. }[/math]

Since [math]\displaystyle{ (X-\mathbf{E}[X])^2 }[/math] is a nonnegative random variable, we can apply Markov's inequality, such that

- [math]\displaystyle{ \Pr[(X-\mathbf{E}[X])^2 \ge t^2] \le \frac{\mathbf{E}[(X-\mathbf{E}[X])^2]}{t^2} =\frac{\mathbf{Var}[X]}{t^2}. }[/math]

[math]\displaystyle{ \square }[/math]