Combinatorics (Fall 2010)/Generating functions: Difference between revisions

imported>WikiSysop m Protected "Combinatorics (Fall 2010)/Generating functions" ([edit=sysop] (indefinite) [move=sysop] (indefinite)) |

|||

| (50 intermediate revisions by 8 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

== Generating Functions == | == Generating Functions == | ||

In Stanley's magnificent book ''Enumerative Combinatorics'', he comments the generating function as "the most useful but most difficult to understand method (for counting)". | In Stanley's magnificent book ''Enumerative Combinatorics'', he comments the generating function as "the most useful but most difficult to understand method (for counting)". | ||

| Line 67: | Line 20: | ||

The true power of generating functions comes from the various algebraic operations that we can perform on these generating functions. We use an example to demonstrate this. | The true power of generating functions comes from the various algebraic operations that we can perform on these generating functions. We use an example to demonstrate this. | ||

=== Combinations === | |||

Suppose we wish to enumerate all subsets of an <math>n</math>-set. To construct a subset, we specifies for every element of the <math>n</math>-set whether the element is chosen or not. Let us denote the choice to omit an element by <math>x_0</math>, and the choice to include it by <math>x_1</math>. Using "<math>+</math>" to represent "OR", and using the multiplication to denote "AND", the choices of subsets of the <math>n</math>-set are expressed as | |||

:<math>\underbrace{(x_0+x_1)(x_0+x_1)\cdots (x_0+x_1)}_{n\mbox{ elements}}=(x_0+x_1)^n</math>. | |||

For example, when <math>n=3</math>, we have | |||

:<math>\begin{align} | |||

(x_0+x_1)^3 | |||

&=x_0x_0x_0+x_0x_0x_1+x_0x_1x_0+x_0x_1x_1\\ | |||

&\quad +x_1x_0x_0+x_1x_0x_1+x_1x_1x_0+x_1x_1x_1 | |||

\end{align}</math>. | |||

So it "generate" all subsets of the 3-set. Writing <math>1</math> for <math>x_0</math> and <math>x</math> for <math>x_1</math>, we have <math>(1+x)^3=1+3x+3x^2+x^3</math>. The coefficient of <math>x^k</math> is the number of <math>k</math>-subsets of a 3-element set. | |||

In general, <math>(1+x)^n</math> has the coefficients which are the number of subsets of fixed sizes of an <math>n</math>-element set. | |||

----- | |||

Suppose that we have twelve balls: <font color="red">3 red</font>, <font color="blue">4 blue</font>, and <font color="green">5 green</font>. Balls with the same color are indistinguishable. | |||

We want to determine the number of ways to select <math>k</math> balls from these twelve balls, for some <math>0\le k\le 12</math>. | |||

The generating function of this sequence is | |||

:<math>\begin{align} | |||

&\quad {\color{Red}(1+x+x^2+x^3)}{\color{Blue}(1+x+x^2+x^3+x^4)}{\color{OliveGreen}(1+x+x^2+x^3+x^4+x^5)}\\ | |||

&=1+3x+6x^2+10x^3+14x^4+17x^5+18x^6+17x^7+14x^8+10x^9+6x^{10}+3x^{11}+x^{12}. | |||

\end{align}</math> | |||

The coefficient of <math>x^k</math> gives the number of ways to select <math>k</math> balls. | |||

=== Fibonacci numbers === | === Fibonacci numbers === | ||

Consider the following counting problems. | Consider the following counting problems. | ||

* Count the number of ways that the nonnegative integer <math>n</math> can be written as a sum of ones and twos (in order). | * Count the number of ways that the nonnegative integer <math>n</math> can be written as a sum of ones and twos (in order). | ||

: The problem asks for the number of compositions of <math>n</math> with summands from <math>\{1,2\}</math>. Formally, we are counting the number of tuples <math>(x_1,x_2,\ldots,x_k)</math> for some <math>k\le n</math> such that <math>x_i\in\{1,2\}</math> and <math>\ | : The problem asks for the number of compositions of <math>n</math> with summands from <math>\{1,2\}</math>. Formally, we are counting the number of tuples <math>(x_1,x_2,\ldots,x_k)</math> for some <math>k\le n</math> such that <math>x_i\in\{1,2\}</math> and <math>x_1+x_2+\cdots+x_k=n</math>. | ||

: Let <math>F_n</math> be the solution. We observe that a composition either starts with a 1, in which case the rest is a composition of <math>n-1</math>; or starts with a 2, in which case the rest is a composition of <math>n-2</math>. So we have the recursion for <math>F_n</math> that | : Let <math>F_n</math> be the solution. We observe that a composition either starts with a 1, in which case the rest is a composition of <math>n-1</math>; or starts with a 2, in which case the rest is a composition of <math>n-2</math>. So we have the recursion for <math>F_n</math> that | ||

::<math>F_n=F_{n-1}+F_{n-2}</math>. | ::<math>F_n=F_{n-1}+F_{n-2}</math>. | ||

| Line 80: | Line 61: | ||

In both problems, the solution is given by <math>F_n</math> which satisfies the following recursion. | In both problems, the solution is given by <math>F_n</math> which satisfies the following recursion. | ||

:<math>F_n=\begin{cases} | :<math>F_n=\begin{cases} | ||

F_{n-1}+F_{n-2} & \mbox{if }n\ge 2,\\ | |||

1 & \mbox{if }n=1\\ | 1 & \mbox{if }n=1\\ | ||

0 & \mbox{if }n=0. | |||

\end{cases}</math> | \end{cases}</math> | ||

| Line 94: | Line 75: | ||

We now prove this theorem by using generating functions. | We now prove this theorem by using generating functions. | ||

The ordinary generating function for the Fibonacci number <math>F_{n}</math> is | The ordinary generating function for the Fibonacci number <math>F_{n}</math> is | ||

:<math>G(x)=\sum_{n\ge 0}F_n x^n</math>. | :<math>G(x)=\sum_{n\ge 0}F_n x^n</math>. | ||

| Line 102: | Line 82: | ||

&= | &= | ||

\sum_{n\ge 0}F_n x^n | \sum_{n\ge 0}F_n x^n | ||

&= | |||

F_0+F_1x+\sum_{n\ge 2}F_n x^n | |||

&= | &= | ||

x+\sum_{n\ge 2}(F_{n-1}+F_{n-2})x^n. | x+\sum_{n\ge 2}(F_{n-1}+F_{n-2})x^n. | ||

| Line 122: | Line 104: | ||

---- | ---- | ||

It is easier to expand the generating function by breaking it into two geometric series. | |||

{{Theorem|Proposition| | |||

:Let <math>\phi=\frac{1+\sqrt{5}}{2}</math> and <math>\hat{\phi}=\frac{1-\sqrt{5}}{2}</math>. It holds that | |||

::<math>\frac{x}{1-x-x^2}=\frac{1}{\sqrt{5}}\cdot\frac{1}{1-\phi x}-\frac{1}{\sqrt{5}}\cdot\frac{1}{1-\hat{\phi} x}</math>. | |||

}} | |||

It is easy to verify the above equation, but to deduce it, we need some (high school) calculation. | |||

{|border="2" width="100%" cellspacing="4" cellpadding="3" rules="all" style="margin:1em 1em 1em 0; border:solid 1px #AAAAAA; border-collapse:collapse;empty-cells:show;" | |||

| | |||

:{| | |||

| | |||

<math>1-x-x^2</math> has two roots <math>\frac{-1\pm\sqrt{5}}{2}</math>. | <math>1-x-x^2</math> has two roots <math>\frac{-1\pm\sqrt{5}}{2}</math>. | ||

Denote that <math>\phi=\frac{2}{-1+\sqrt{5}}=\frac{1+\sqrt{5}}{2}</math> and <math>\hat{\phi}=\frac{2}{-1-\sqrt{5}}=\frac{1-\sqrt{5}}{2}</math>. Then <math>(1-x-x^2)=(1-\phi x)(1-\hat{\phi}x)</math>, so we can write | Denote that <math>\phi=\frac{2}{-1+\sqrt{5}}=\frac{1+\sqrt{5}}{2}</math> and <math>\hat{\phi}=\frac{2}{-1-\sqrt{5}}=\frac{1-\sqrt{5}}{2}</math>. | ||

Then <math>(1-x-x^2)=(1-\phi x)(1-\hat{\phi}x)</math>, so we can write | |||

:<math> | :<math> | ||

\begin{align} | \begin{align} | ||

| Line 139: | Line 133: | ||

\alpha\phi+\beta\hat{\phi}= -1. | \alpha\phi+\beta\hat{\phi}= -1. | ||

\end{cases}</math> | \end{cases}</math> | ||

Solving this we have that <math>\alpha=\frac{1}{\sqrt{5}}</math> and <math>\beta=-\frac{1}{\sqrt{5}}</math>. | Solving this we have that <math>\alpha=\frac{1}{\sqrt{5}}</math> and <math>\beta=-\frac{1}{\sqrt{5}}</math>. Thus, | ||

:<math>G(x)=\frac{x}{1-x-x^2}=\frac{1}{\sqrt{5}}\cdot\frac{1}{1-\phi x}-\frac{1}{\sqrt{5}}\cdot\frac{1}{1-\hat{\phi} x}</math> | :<math>G(x)=\frac{x}{1-x-x^2}=\frac{1}{\sqrt{5}}\cdot\frac{1}{1-\phi x}-\frac{1}{\sqrt{5}}\cdot\frac{1}{1-\hat{\phi} x}</math>. | ||

|} | |||

:<math>\square</math> | |||

|} | |||

Note that the expression <math>\frac{1}{1-z}</math> has a well known expansion: | Note that the expression <math>\frac{1}{1-z}</math> has a well known geometric expansion: | ||

:<math>\frac{1}{1-z}=\sum_{n\ge 0}z^n</math>. | :<math>\frac{1}{1-z}=\sum_{n\ge 0}z^n</math>. | ||

| Line 157: | Line 153: | ||

:<math>F_n=\frac{1}{\sqrt{5}}\left(\phi^n-\hat{\phi}^n\right)=\frac{1}{\sqrt{5}}\left(\frac{1+\sqrt{5}}{2}\right)^n-\frac{1}{\sqrt{5}}\left(\frac{1-\sqrt{5}}{2}\right)^n</math>. | :<math>F_n=\frac{1}{\sqrt{5}}\left(\phi^n-\hat{\phi}^n\right)=\frac{1}{\sqrt{5}}\left(\frac{1+\sqrt{5}}{2}\right)^n-\frac{1}{\sqrt{5}}\left(\frac{1-\sqrt{5}}{2}\right)^n</math>. | ||

== Solving recurrences == | |||

The following steps describe a general methodology of solving recurrences by generating functions. | |||

:1. Give a recursion that computes <math>a_n</math> | :1. Give a recursion that computes <math>a_n</math>. In the case of Fibonacci sequence | ||

::<math>a_n= | ::<math>a_n=a_{n-1}+a_{n-2}</math>. | ||

:2. Multiply both sides of the equation by <math>x^n</math> and sum over all <math>n</math>. This gives the generating function | :2. Multiply both sides of the equation by <math>x^n</math> and sum over all <math>n</math>. This gives the generating function | ||

::<math>G(x)=\sum_{n\ge 0}a_nx^n=\sum_{n\ge 0} | ::<math>G(x)=\sum_{n\ge 0}a_nx^n=\sum_{n\ge 0}(a_{n-1}+a_{n-2})x^n</math>. | ||

:: And manipulate the right hand side of the equation so that it becomes some other expression involving <math>G(x)</math>. | :: And manipulate the right hand side of the equation so that it becomes some other expression involving <math>G(x)</math>. | ||

::<math>G(x)=x+(x+x^2)G(x)\,</math>. | |||

:3. Solve the resulting equation to derive an explicit formula for <math>G(x)</math>. | :3. Solve the resulting equation to derive an explicit formula for <math>G(x)</math>. | ||

::<math>G(x)=\frac{x}{1-x-x^2}</math>. | |||

:4. Expand <math>G(x)</math> into a power series and read off the coefficient of <math>x^n</math>, which is a closed form for <math>a_n</math>. | :4. Expand <math>G(x)</math> into a power series and read off the coefficient of <math>x^n</math>, which is a closed form for <math>a_n</math>. | ||

The first step is usually established by combinatorial observations, or explicitly given by the problem. The third step is trivial. | |||

The second and the forth steps need some non-trivial analytic techniques. | |||

=== Algebraic operations on generating functions === | |||

The second step in the above methodology is somehow tricky. It involves first applying the recurrence to the coefficients of <math>G(x)</math>, which is easy; and then manipulating the resulting formal power series to express it in terms of <math>G(x)</math>, which is more difficult (because it works backwards). | The second step in the above methodology is somehow tricky. It involves first applying the recurrence to the coefficients of <math>G(x)</math>, which is easy; and then manipulating the resulting formal power series to express it in terms of <math>G(x)</math>, which is more difficult (because it works backwards). | ||

| Line 181: | Line 183: | ||

x^k G(x) | x^k G(x) | ||

&= \sum_{n\ge k}g_{n-k}x^n, &\qquad (\mbox{integer }k\ge 0)\\ | &= \sum_{n\ge k}g_{n-k}x^n, &\qquad (\mbox{integer }k\ge 0)\\ | ||

\frac{G(x)-\sum_{i=0}^{k-1} | \frac{G(x)-\sum_{i=0}^{k-1}g_ix^i}{x^k} | ||

&=\sum_{n\ge 0}g_{n+k}x^n, &\qquad (\mbox{integer }k\ge 0)\\ | &=\sum_{n\ge 0}g_{n+k}x^n, &\qquad (\mbox{integer }k\ge 0)\\ | ||

\alpha F(x)+\beta G(x) | \alpha F(x)+\beta G(x) | ||

| Line 191: | Line 193: | ||

G'(x) | G'(x) | ||

&= | &= | ||

\sum_{n\ge 0}(n+1)g_{n+1} | \sum_{n\ge 0}(n+1)g_{n+1}x^n | ||

\end{align} | \end{align} | ||

</math> | </math> | ||

| Line 200: | Line 200: | ||

When manipulating generating functions, these rules are applied backwards; that is, from the right-hand-side to the left-hand-side. | When manipulating generating functions, these rules are applied backwards; that is, from the right-hand-side to the left-hand-side. | ||

=== Expanding generating functions === | |||

The last step of solving recurrences by generating function is expanding the closed form generating function <math>G(x)</math> to evaluate its <math>n</math>-th coefficient. In principle, we can always use the [http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Taylor_series Taylor series] | The last step of solving recurrences by generating function is expanding the closed form generating function <math>G(x)</math> to evaluate its <math>n</math>-th coefficient. In principle, we can always use the [http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Taylor_series Taylor series] | ||

:<math>G(x)=\sum_{n\ge 0}\frac{G^{(n)}(0)}{n!}x^n</math>, | :<math>G(x)=\sum_{n\ge 0}\frac{G^{(n)}(0)}{n!}x^n</math>, | ||

| Line 207: | Line 207: | ||

Some interesting special cases are very useful. | Some interesting special cases are very useful. | ||

====Geometric sequence==== | |||

In the example of Fibonacci numbers, we use the well known geometric series: | In the example of Fibonacci numbers, we use the well known geometric series: | ||

:<math>\frac{1}{1-x}=\sum_{n\ge 0}x^n</math>. | :<math>\frac{1}{1-x}=\sum_{n\ge 0}x^n</math>. | ||

It is useful when we can express the generating function in the form of <math>G(x)=\frac{a_1}{1-b_1x}+\frac{a_2}{1-b_2x}+\cdots+\frac{a_k}{1-b_kx}</math>. The coefficient of <math>x^n</math> in such <math>G(x)</math> is <math>a_1b_1^n+a_2b_2^n+\cdots+a_kb_k^n</math>. | It is useful when we can express the generating function in the form of <math>G(x)=\frac{a_1}{1-b_1x}+\frac{a_2}{1-b_2x}+\cdots+\frac{a_k}{1-b_kx}</math>. The coefficient of <math>x^n</math> in such <math>G(x)</math> is <math>a_1b_1^n+a_2b_2^n+\cdots+a_kb_k^n</math>. | ||

====Binomial theorem==== | |||

The <math>n</math>-th derivative of <math>(1+x)^\alpha</math> for some real <math>\alpha</math> is | The <math>n</math>-th derivative of <math>(1+x)^\alpha</math> for some real <math>\alpha</math> is | ||

:<math>\alpha(\alpha-1)(\alpha-2)\cdots(\alpha-n+1)(1+x)^{\alpha-n}</math>. | :<math>\alpha(\alpha-1)(\alpha-2)\cdots(\alpha-n+1)(1+x)^{\alpha-n}</math>. | ||

By Taylor series, we get a generalized version of the binomial theorem known as [http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Binomial_coefficient#Newton.27s_binomial_series '''Newton's formula''']: | By Taylor series, we get a generalized version of the binomial theorem known as [http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Binomial_coefficient#Newton.27s_binomial_series '''Newton's formula''']: | ||

{{Theorem|Newton's formular (generalized binomial theorem)| | |||

If <math>|x|<1</math>, then | |||

:<math>(1+x)^\alpha=\sum_{n\ge 0}{\alpha\choose n}x^{n}</math>, | :<math>(1+x)^\alpha=\sum_{n\ge 0}{\alpha\choose n}x^{n}</math>, | ||

where <math>{\alpha\choose n}</math> is the '''generalized binomial coefficient''' defined by | where <math>{\alpha\choose n}</math> is the '''generalized binomial coefficient''' defined by | ||

:<math>{\alpha\choose n}=\frac{\alpha(\alpha-1)(\alpha-2)\cdots(\alpha-n+1)}{n!}</math>. | :<math>{\alpha\choose n}=\frac{\alpha(\alpha-1)(\alpha-2)\cdots(\alpha-n+1)}{n!}</math>. | ||

}} | |||

=== Example: multisets === | |||

In the last lecture we gave a combinatorial proof of the number of <math>k</math>-multisets on an <math>n</math>-set. Now we give a generating function approach to the problem. | In the last lecture we gave a combinatorial proof of the number of <math>k</math>-multisets on an <math>n</math>-set. Now we give a generating function approach to the problem. | ||

| Line 248: | Line 253: | ||

</math> | </math> | ||

The last equation is due to the definition of the generalized binomial coefficient. We use an analytic (generating function) proof to get the same result of <math>\left({n\choose k}\right)</math> as the combinatorial proof. | The last equation is due to the definition of the generalized binomial coefficient. We use an analytic (generating function) proof to get the same result of <math>\left({n\choose k}\right)</math> as the combinatorial proof. | ||

== Catalan Number == | |||

We now introduce a class of counting problems, all with the same solution, called [http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Catalan_number '''Catalan number''']. | |||

The <math>n</math>th Catalan number is denoted as <math>C_n</math>. | |||

In Volume 2 of Stanley's ''Enumerative Combinatorics'', a set of exercises describe 66 different interpretations of the Catalan numbers. We give a few examples, cited from Wikipedia. | |||

* ''C''<sub>''n''</sub> is the number of '''Dyck words''' of length 2''n''. A Dyck word is a string consisting of ''n'' X's and ''n'' Y's such that no initial segment of the string has more Y's than X's (see also [http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dyck_language Dyck language]). For example, the following are the Dyck words of length 6: | |||

<div class="center"><big> XXXYYY XYXXYY XYXYXY XXYYXY XXYXYY.</big></div> | |||

* Re-interpreting the symbol X as an open parenthesis and Y as a close parenthesis, ''C''<sub>''n''</sub> counts the number of expressions containing ''n'' pairs of parentheses which are correctly matched: | |||

<div class="center"><big> ((())) ()(()) ()()() (())() (()()) </big></div> | |||

* ''C''<sub>''n''</sub> is the number of different ways ''n'' + 1 factors can be completely parenthesized (or the number of ways of associating ''n'' applications of a '''binary operator'''). For ''n'' = 3, for example, we have the following five different parenthesizations of four factors: | |||

<div class="center"><math>((ab)c)d \quad (a(bc))d \quad(ab)(cd) \quad a((bc)d) \quad a(b(cd))</math></div> | |||

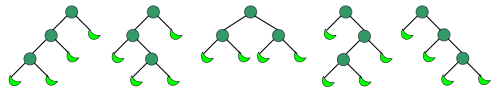

* Successive applications of a binary operator can be represented in terms of a '''full binary tree'''. (A rooted binary tree is ''full'' if every vertex has either two children or no children.) It follows that ''C''<sub>''n''</sub> is the number of full binary trees with ''n'' + 1 leaves: | |||

[[Image:Catalan number binary tree example.png|center]] | |||

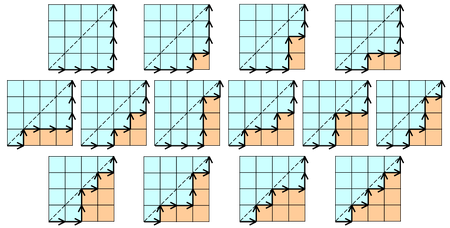

* ''C''<sub>''n''</sub> is the number of '''monotonic paths''' along the edges of a grid with ''n'' × ''n'' square cells, which do not pass above the diagonal. A monotonic path is one which starts in the lower left corner, finishes in the upper right corner, and consists entirely of edges pointing rightwards or upwards. Counting such paths is equivalent to counting Dyck words: X stands for "move right" and Y stands for "move up". The following diagrams show the case ''n'' = 4: | |||

[[Image:Catalan number 4x4 grid example.svg.png|450px|center]] | |||

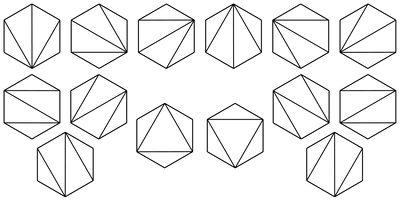

* ''C''<sub>''n''</sub> is the number of different ways a [http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Convex_polygon '''convex polygon'''] with ''n'' + 2 sides can be cut into '''triangles''' by connecting vertices with straight lines. The following hexagons illustrate the case ''n'' = 4: | |||

[[Image:Catalan-Hexagons-example.png|400px|center]] | |||

* ''C''<sub>''n''</sub> is the number of [http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Stack_(data_structure) '''stack''']-sortable permutations of {1, ..., ''n''}. A permutation ''w'' is called '''stack-sortable''' if ''S''(''w'') = (1, ..., ''n''), where ''S''(''w'') is defined recursively as follows: write ''w'' = ''unv'' where ''n'' is the largest element in ''w'' and ''u'' and ''v'' are shorter sequences, and set ''S''(''w'') = ''S''(''u'')''S''(''v'')''n'', with ''S'' being the identity for one-element sequences. | |||

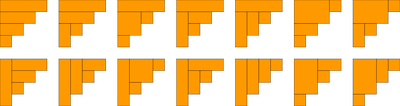

* ''C''<sub>''n''</sub> is the number of ways to tile a stairstep shape of height ''n'' with ''n'' rectangles. The following figure illustrates the case ''n'' = 4: | |||

[[Image:Catalan stairsteps 4.png|400px|center]] | |||

=== Solving the Catalan numbers === | |||

{{Theorem|Recurrence relation for Catalan numbers| | |||

:<math>C_0=1</math>, and for <math>n\ge1</math>, | |||

::<math> | |||

C_n= | |||

\sum_{k=0}^{n-1}C_kC_{n-1-k}</math>. | |||

}} | |||

Let <math>G(x)=\sum_{n\ge 0}C_nx^n</math> be the generating function. Then | |||

:<math> | |||

\begin{align} | |||

G(x)^2 | |||

&=\sum_{n\ge 0}\sum_{k=0}^{n}C_kC_{n-k}x^n\\ | |||

xG(x)^2 | |||

&=\sum_{n\ge 0}\sum_{k=0}^{n}C_kC_{n-k}x^{n+1}=\sum_{n\ge 1}\sum_{k=0}^{n-1}C_kC_{n-1-k}x^n. | |||

\end{align} | |||

</math> | |||

Due to the recurrence, | |||

:<math>G(x)=\sum_{n\ge 0}C_nx^n=C_0+\sum_{n\ge 1}\sum_{k=0}^{n-1}C_kC_{n-1-k}x^n=1+xG(x)^2</math>. | |||

Solving <math>xG(x)^2-G(x)+1=0</math>, we obtain | |||

:<math>G(x)=\frac{1\pm(1-4x)^{1/2}}{2x}</math>. | |||

Only one of these functions can be the generating function for <math>C_n</math>, and it must satisfy | |||

:<math>\lim_{x\rightarrow 0}G(x)=C_0=1</math>. | |||

It is easy to check that the correct function is | |||

:<math>G(x)=\frac{1-(1-4x)^{1/2}}{2x}</math>. | |||

Expanding <math>(1-4x)^{1/2}</math> by Newton's formula, | |||

:<math> | |||

\begin{align} | |||

(1-4x)^{1/2} | |||

&= | |||

\sum_{n\ge 0}{1/2\choose n}(-4x)^n\\ | |||

&= | |||

1+\sum_{n\ge 1}{1/2\choose n}(-4x)^n\\ | |||

&= | |||

1-4x\sum_{n\ge 0}{1/2\choose n+1}(-4x)^n | |||

\end{align} | |||

</math> | |||

Then, we have | |||

:<math> | |||

\begin{align} | |||

G(x) | |||

&= | |||

\frac{1-(1-4x)^{1/2}}{2x}\\ | |||

&= | |||

2\sum_{n\ge 0}{1/2\choose n+1}(-4x)^n | |||

\end{align} | |||

</math> | |||

Thus, | |||

:<math> | |||

\begin{align} | |||

C_n | |||

&=2{1/2\choose n+1}(-4)^n\\ | |||

&=2\cdot\left(\frac{1}{2}\cdot\frac{-1}{2}\cdot\frac{-3}{2}\cdots\frac{-(2n-1)}{2}\right)\cdot\frac{1}{(n+1)!}\cdot(-4)^n\\ | |||

&=\frac{2^n}{(n+1)!}\prod_{k=1}^n(2k-1)\\ | |||

&=\frac{2^n}{(n+1)!}\prod_{k=1}^n\frac{(2k-1)2k}{2k}\\ | |||

&=\frac{1}{n!(n+1)!}\prod_{k=1}^n (2k-1)2k\\ | |||

&=\frac{(2n)!}{n!(n+1)!}\\ | |||

&=\frac{1}{n+1}{2n\choose n}. | |||

\end{align} | |||

</math> | |||

So we prove the following closed form for Catalan number. | |||

{{Theorem|Theorem| | |||

:<math>C_n=\frac{1}{n+1}{2n\choose n}</math>. | |||

}} | |||

== Reference == | |||

* ''Graham, Knuth, and Patashnik'', Concrete Mathematics: A Foundation for Computer Science, Chapter 7. | |||

* ''Cameron'', Combinatorics: Topics, Techniques, Algorithms, Chapter 4. | |||

* ''van Lin and Wilson'', A course in combinatorics, Chapter 14. | |||

Latest revision as of 04:53, 7 October 2010

Generating Functions

In Stanley's magnificent book Enumerative Combinatorics, he comments the generating function as "the most useful but most difficult to understand method (for counting)".

The solution to a counting problem is usually represented as some [math]\displaystyle{ a_n }[/math] depending a parameter [math]\displaystyle{ n }[/math]. Sometimes this [math]\displaystyle{ a_n }[/math] is called a counting function as it is a function of the parameter [math]\displaystyle{ n }[/math]. [math]\displaystyle{ a_n }[/math] can also be treated as a infinite series:

- [math]\displaystyle{ a_0,a_1,a_2,\ldots }[/math]

The ordinary generating function (OGF) defined by [math]\displaystyle{ a_n }[/math] is

- [math]\displaystyle{ G(x)=\sum_{n\ge 0} a_nx^n. }[/math]

So [math]\displaystyle{ G(x)=a_0+a_1x+a_2x^2+\cdots }[/math]. An expression in this form is called a formal power series, and [math]\displaystyle{ a_0,a_1,a_2,\ldots }[/math] is the sequence of coefficients.

Furthermore, the generating function can be expanded as

- G(x)=[math]\displaystyle{ (\underbrace{1+\cdots+1}_{a_0})+(\underbrace{x+\cdots+x}_{a_1})+(\underbrace{x^2+\cdots+x^2}_{a_2})+\cdots+(\underbrace{x^n+\cdots+x^n}_{a_n})+\cdots }[/math]

so it indeed "generates" all the possible instances of the objects we want to count.

Usually, we do not evaluate the generating function [math]\displaystyle{ GF(x) }[/math] on any particular value. [math]\displaystyle{ x }[/math] remains as a formal variable without assuming any value. The numbers that we want to count are the coefficients carried by the terms in the formal power series. So far the generating function is just another way to represent the sequence

- [math]\displaystyle{ (a_0,a_1,a_2,\ldots\ldots) }[/math].

The true power of generating functions comes from the various algebraic operations that we can perform on these generating functions. We use an example to demonstrate this.

Combinations

Suppose we wish to enumerate all subsets of an [math]\displaystyle{ n }[/math]-set. To construct a subset, we specifies for every element of the [math]\displaystyle{ n }[/math]-set whether the element is chosen or not. Let us denote the choice to omit an element by [math]\displaystyle{ x_0 }[/math], and the choice to include it by [math]\displaystyle{ x_1 }[/math]. Using "[math]\displaystyle{ + }[/math]" to represent "OR", and using the multiplication to denote "AND", the choices of subsets of the [math]\displaystyle{ n }[/math]-set are expressed as

- [math]\displaystyle{ \underbrace{(x_0+x_1)(x_0+x_1)\cdots (x_0+x_1)}_{n\mbox{ elements}}=(x_0+x_1)^n }[/math].

For example, when [math]\displaystyle{ n=3 }[/math], we have

- [math]\displaystyle{ \begin{align} (x_0+x_1)^3 &=x_0x_0x_0+x_0x_0x_1+x_0x_1x_0+x_0x_1x_1\\ &\quad +x_1x_0x_0+x_1x_0x_1+x_1x_1x_0+x_1x_1x_1 \end{align} }[/math].

So it "generate" all subsets of the 3-set. Writing [math]\displaystyle{ 1 }[/math] for [math]\displaystyle{ x_0 }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ x }[/math] for [math]\displaystyle{ x_1 }[/math], we have [math]\displaystyle{ (1+x)^3=1+3x+3x^2+x^3 }[/math]. The coefficient of [math]\displaystyle{ x^k }[/math] is the number of [math]\displaystyle{ k }[/math]-subsets of a 3-element set.

In general, [math]\displaystyle{ (1+x)^n }[/math] has the coefficients which are the number of subsets of fixed sizes of an [math]\displaystyle{ n }[/math]-element set.

Suppose that we have twelve balls: 3 red, 4 blue, and 5 green. Balls with the same color are indistinguishable.

We want to determine the number of ways to select [math]\displaystyle{ k }[/math] balls from these twelve balls, for some [math]\displaystyle{ 0\le k\le 12 }[/math].

The generating function of this sequence is

- [math]\displaystyle{ \begin{align} &\quad {\color{Red}(1+x+x^2+x^3)}{\color{Blue}(1+x+x^2+x^3+x^4)}{\color{OliveGreen}(1+x+x^2+x^3+x^4+x^5)}\\ &=1+3x+6x^2+10x^3+14x^4+17x^5+18x^6+17x^7+14x^8+10x^9+6x^{10}+3x^{11}+x^{12}. \end{align} }[/math]

The coefficient of [math]\displaystyle{ x^k }[/math] gives the number of ways to select [math]\displaystyle{ k }[/math] balls.

Fibonacci numbers

Consider the following counting problems.

- Count the number of ways that the nonnegative integer [math]\displaystyle{ n }[/math] can be written as a sum of ones and twos (in order).

- The problem asks for the number of compositions of [math]\displaystyle{ n }[/math] with summands from [math]\displaystyle{ \{1,2\} }[/math]. Formally, we are counting the number of tuples [math]\displaystyle{ (x_1,x_2,\ldots,x_k) }[/math] for some [math]\displaystyle{ k\le n }[/math] such that [math]\displaystyle{ x_i\in\{1,2\} }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ x_1+x_2+\cdots+x_k=n }[/math].

- Let [math]\displaystyle{ F_n }[/math] be the solution. We observe that a composition either starts with a 1, in which case the rest is a composition of [math]\displaystyle{ n-1 }[/math]; or starts with a 2, in which case the rest is a composition of [math]\displaystyle{ n-2 }[/math]. So we have the recursion for [math]\displaystyle{ F_n }[/math] that

- [math]\displaystyle{ F_n=F_{n-1}+F_{n-2} }[/math].

- Count the ways to completely cover a [math]\displaystyle{ 2\times n }[/math] rectangle with [math]\displaystyle{ 2\times 1 }[/math] dominos without any overlaps.

- Dominos are identical [math]\displaystyle{ 2\times 1 }[/math] rectangles, so that only their orientations --- vertical or horizontal matter.

- Let [math]\displaystyle{ F_n }[/math] be the solution. It also holds that [math]\displaystyle{ F_n=F_{n-1}+F_{n-2} }[/math]. The proof is left as an exercise.

In both problems, the solution is given by [math]\displaystyle{ F_n }[/math] which satisfies the following recursion.

- [math]\displaystyle{ F_n=\begin{cases} F_{n-1}+F_{n-2} & \mbox{if }n\ge 2,\\ 1 & \mbox{if }n=1\\ 0 & \mbox{if }n=0. \end{cases} }[/math]

[math]\displaystyle{ F_n }[/math] is called the Fibonacci number.

Theorem - [math]\displaystyle{ F_n=\frac{1}{\sqrt{5}}\left(\phi^n-\hat{\phi}^n\right) }[/math],

- where [math]\displaystyle{ \phi=\frac{1+\sqrt{5}}{2} }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ \hat{\phi}=\frac{1-\sqrt{5}}{2} }[/math].

The quantity [math]\displaystyle{ \phi=\frac{1+\sqrt{5}}{2} }[/math] is the so-called golden ratio, a constant with some significance in mathematics and aesthetics.

We now prove this theorem by using generating functions. The ordinary generating function for the Fibonacci number [math]\displaystyle{ F_{n} }[/math] is

- [math]\displaystyle{ G(x)=\sum_{n\ge 0}F_n x^n }[/math].

We have that [math]\displaystyle{ F_{n}=F_{n-1}+F_{n-2} }[/math] for [math]\displaystyle{ n\ge 2 }[/math], thus

- [math]\displaystyle{ \begin{align} G(x) &= \sum_{n\ge 0}F_n x^n &= F_0+F_1x+\sum_{n\ge 2}F_n x^n &= x+\sum_{n\ge 2}(F_{n-1}+F_{n-2})x^n. \end{align} }[/math]

For generating functions, there are general ways to generate [math]\displaystyle{ F_{n-1} }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ F_{n-2} }[/math], or the coefficients with any smaller indices.

- [math]\displaystyle{ \begin{align} xG(x) &=\sum_{n\ge 0}F_n x^{n+1}=\sum_{n\ge 1}F_{n-1} x^n=\sum_{n\ge 2}F_{n-1} x^n\\ x^2G(x) &=\sum_{n\ge 0}F_n x^{n+2}=\sum_{n\ge 2}F_{n-2} x^n. \end{align} }[/math]

So we have

- [math]\displaystyle{ G(x)=x+(x+x^2)G(x)\, }[/math],

hence

- [math]\displaystyle{ G(x)=\frac{x}{1-x-x^2} }[/math].

The value of [math]\displaystyle{ F_n }[/math] is the coefficient of [math]\displaystyle{ x^n }[/math] in the Taylor series for this formular, which is [math]\displaystyle{ \frac{G^{(n)}(0)}{n!}=\frac{1}{\sqrt{5}}\left(\frac{1+\sqrt{5}}{2}\right)^n-\frac{1}{\sqrt{5}}\left(\frac{1-\sqrt{5}}{2}\right)^n }[/math]. Although this expansion works in principle, the detailed calculus is rather painful.

It is easier to expand the generating function by breaking it into two geometric series.

Proposition - Let [math]\displaystyle{ \phi=\frac{1+\sqrt{5}}{2} }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ \hat{\phi}=\frac{1-\sqrt{5}}{2} }[/math]. It holds that

- [math]\displaystyle{ \frac{x}{1-x-x^2}=\frac{1}{\sqrt{5}}\cdot\frac{1}{1-\phi x}-\frac{1}{\sqrt{5}}\cdot\frac{1}{1-\hat{\phi} x} }[/math].

- Let [math]\displaystyle{ \phi=\frac{1+\sqrt{5}}{2} }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ \hat{\phi}=\frac{1-\sqrt{5}}{2} }[/math]. It holds that

It is easy to verify the above equation, but to deduce it, we need some (high school) calculation.

|

Note that the expression [math]\displaystyle{ \frac{1}{1-z} }[/math] has a well known geometric expansion:

- [math]\displaystyle{ \frac{1}{1-z}=\sum_{n\ge 0}z^n }[/math].

Therefore, [math]\displaystyle{ G(x) }[/math] can be expanded as

- [math]\displaystyle{ \begin{align} G(x) &=\frac{1}{\sqrt{5}}\cdot\frac{1}{1-\phi x}-\frac{1}{\sqrt{5}}\cdot\frac{1}{1-\hat{\phi} x}\\ &=\frac{1}{\sqrt{5}}\sum_{n\ge 0}(\phi x)^n-\frac{1}{\sqrt{5}}\sum_{n\ge 0}(\hat{\phi} x)^n\\ &=\sum_{n\ge 0}\frac{1}{\sqrt{5}}\left(\phi^n-\hat{\phi}^n\right)x^n. \end{align} }[/math]

So the [math]\displaystyle{ n }[/math]th Fibonacci number is given by

- [math]\displaystyle{ F_n=\frac{1}{\sqrt{5}}\left(\phi^n-\hat{\phi}^n\right)=\frac{1}{\sqrt{5}}\left(\frac{1+\sqrt{5}}{2}\right)^n-\frac{1}{\sqrt{5}}\left(\frac{1-\sqrt{5}}{2}\right)^n }[/math].

Solving recurrences

The following steps describe a general methodology of solving recurrences by generating functions.

- 1. Give a recursion that computes [math]\displaystyle{ a_n }[/math]. In the case of Fibonacci sequence

- [math]\displaystyle{ a_n=a_{n-1}+a_{n-2} }[/math].

- 2. Multiply both sides of the equation by [math]\displaystyle{ x^n }[/math] and sum over all [math]\displaystyle{ n }[/math]. This gives the generating function

- [math]\displaystyle{ G(x)=\sum_{n\ge 0}a_nx^n=\sum_{n\ge 0}(a_{n-1}+a_{n-2})x^n }[/math].

- And manipulate the right hand side of the equation so that it becomes some other expression involving [math]\displaystyle{ G(x) }[/math].

- [math]\displaystyle{ G(x)=x+(x+x^2)G(x)\, }[/math].

- 3. Solve the resulting equation to derive an explicit formula for [math]\displaystyle{ G(x) }[/math].

- [math]\displaystyle{ G(x)=\frac{x}{1-x-x^2} }[/math].

- 4. Expand [math]\displaystyle{ G(x) }[/math] into a power series and read off the coefficient of [math]\displaystyle{ x^n }[/math], which is a closed form for [math]\displaystyle{ a_n }[/math].

The first step is usually established by combinatorial observations, or explicitly given by the problem. The third step is trivial.

The second and the forth steps need some non-trivial analytic techniques.

Algebraic operations on generating functions

The second step in the above methodology is somehow tricky. It involves first applying the recurrence to the coefficients of [math]\displaystyle{ G(x) }[/math], which is easy; and then manipulating the resulting formal power series to express it in terms of [math]\displaystyle{ G(x) }[/math], which is more difficult (because it works backwards).

We can apply several natural algebraic operations on the formal power series.

Generating function manipulation - Let [math]\displaystyle{ G(x)=\sum_{n\ge 0}g_nx^n }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ F(x)=\sum_{n\ge 0}f_nx^n }[/math].

- [math]\displaystyle{ \begin{align} x^k G(x) &= \sum_{n\ge k}g_{n-k}x^n, &\qquad (\mbox{integer }k\ge 0)\\ \frac{G(x)-\sum_{i=0}^{k-1}g_ix^i}{x^k} &=\sum_{n\ge 0}g_{n+k}x^n, &\qquad (\mbox{integer }k\ge 0)\\ \alpha F(x)+\beta G(x) &= \sum_{n\ge 0} (\alpha f_n+\beta g_n)x^n\\ F(x)G(x) &= \sum_{n\ge 0}\sum_{k=0}^nf_kg_{n-k}x^n\\ G(cx) &= \sum_{n\ge 0} c^ng_n x^n\\ G'(x) &= \sum_{n\ge 0}(n+1)g_{n+1}x^n \end{align} }[/math]

When manipulating generating functions, these rules are applied backwards; that is, from the right-hand-side to the left-hand-side.

Expanding generating functions

The last step of solving recurrences by generating function is expanding the closed form generating function [math]\displaystyle{ G(x) }[/math] to evaluate its [math]\displaystyle{ n }[/math]-th coefficient. In principle, we can always use the Taylor series

- [math]\displaystyle{ G(x)=\sum_{n\ge 0}\frac{G^{(n)}(0)}{n!}x^n }[/math],

where [math]\displaystyle{ G^{(n)}(0) }[/math] is the value of the [math]\displaystyle{ n }[/math]-th derivative of [math]\displaystyle{ G(x) }[/math] evaluated at [math]\displaystyle{ x=0 }[/math].

Some interesting special cases are very useful.

Geometric sequence

In the example of Fibonacci numbers, we use the well known geometric series:

- [math]\displaystyle{ \frac{1}{1-x}=\sum_{n\ge 0}x^n }[/math].

It is useful when we can express the generating function in the form of [math]\displaystyle{ G(x)=\frac{a_1}{1-b_1x}+\frac{a_2}{1-b_2x}+\cdots+\frac{a_k}{1-b_kx} }[/math]. The coefficient of [math]\displaystyle{ x^n }[/math] in such [math]\displaystyle{ G(x) }[/math] is [math]\displaystyle{ a_1b_1^n+a_2b_2^n+\cdots+a_kb_k^n }[/math].

Binomial theorem

The [math]\displaystyle{ n }[/math]-th derivative of [math]\displaystyle{ (1+x)^\alpha }[/math] for some real [math]\displaystyle{ \alpha }[/math] is

- [math]\displaystyle{ \alpha(\alpha-1)(\alpha-2)\cdots(\alpha-n+1)(1+x)^{\alpha-n} }[/math].

By Taylor series, we get a generalized version of the binomial theorem known as Newton's formula:

Newton's formular (generalized binomial theorem) If [math]\displaystyle{ |x|\lt 1 }[/math], then

- [math]\displaystyle{ (1+x)^\alpha=\sum_{n\ge 0}{\alpha\choose n}x^{n} }[/math],

where [math]\displaystyle{ {\alpha\choose n} }[/math] is the generalized binomial coefficient defined by

- [math]\displaystyle{ {\alpha\choose n}=\frac{\alpha(\alpha-1)(\alpha-2)\cdots(\alpha-n+1)}{n!} }[/math].

Example: multisets

In the last lecture we gave a combinatorial proof of the number of [math]\displaystyle{ k }[/math]-multisets on an [math]\displaystyle{ n }[/math]-set. Now we give a generating function approach to the problem.

Let [math]\displaystyle{ S=\{x_1,x_2,\ldots,x_n\} }[/math] be an [math]\displaystyle{ n }[/math]-element set. We have

- [math]\displaystyle{ (1+x_1+x_1^2+\cdots)(1+x_2+x_2^2+\cdots)\cdots(1+x_n+x_n^2+\cdots)=\sum_{m:S\rightarrow\mathbb{N}} \prod_{x_i\in S}x_i^{m(x_i)} }[/math],

where each [math]\displaystyle{ m:S\rightarrow\mathbb{N} }[/math] species a possible multiset on [math]\displaystyle{ S }[/math] with multiplicity function [math]\displaystyle{ m }[/math].

Let all [math]\displaystyle{ x_i=x }[/math]. Then

- [math]\displaystyle{ \begin{align} (1+x+x^2+\cdots)^n &= \sum_{m:S\rightarrow\mathbb{N}}x^{m(x_1)+\cdots+m(x_n)}\\ &= \sum_{\text{multiset }M\text{ on }S}x^{|M|}\\ &= \sum_{k\ge 0}\left({n\choose k}\right)x^k. \end{align} }[/math]

The last equation is due to the the definition of [math]\displaystyle{ \left({n\choose k}\right) }[/math]. Our task is to evaluate [math]\displaystyle{ \left({n\choose k}\right) }[/math].

Due to the geometric sequence and the Newton's formula

- [math]\displaystyle{ (1+x+x^2+\cdots)^n=(1-x)^{-n}=\sum_{k\ge 0}{-n\choose k}(-x)^k. }[/math]

So

- [math]\displaystyle{ \left({n\choose k}\right)=(-1)^k{-n\choose k}={n+k-1\choose k}. }[/math]

The last equation is due to the definition of the generalized binomial coefficient. We use an analytic (generating function) proof to get the same result of [math]\displaystyle{ \left({n\choose k}\right) }[/math] as the combinatorial proof.

Catalan Number

We now introduce a class of counting problems, all with the same solution, called Catalan number.

The [math]\displaystyle{ n }[/math]th Catalan number is denoted as [math]\displaystyle{ C_n }[/math]. In Volume 2 of Stanley's Enumerative Combinatorics, a set of exercises describe 66 different interpretations of the Catalan numbers. We give a few examples, cited from Wikipedia.

- Cn is the number of Dyck words of length 2n. A Dyck word is a string consisting of n X's and n Y's such that no initial segment of the string has more Y's than X's (see also Dyck language). For example, the following are the Dyck words of length 6:

- Re-interpreting the symbol X as an open parenthesis and Y as a close parenthesis, Cn counts the number of expressions containing n pairs of parentheses which are correctly matched:

- Cn is the number of different ways n + 1 factors can be completely parenthesized (or the number of ways of associating n applications of a binary operator). For n = 3, for example, we have the following five different parenthesizations of four factors:

- Successive applications of a binary operator can be represented in terms of a full binary tree. (A rooted binary tree is full if every vertex has either two children or no children.) It follows that Cn is the number of full binary trees with n + 1 leaves:

- Cn is the number of monotonic paths along the edges of a grid with n × n square cells, which do not pass above the diagonal. A monotonic path is one which starts in the lower left corner, finishes in the upper right corner, and consists entirely of edges pointing rightwards or upwards. Counting such paths is equivalent to counting Dyck words: X stands for "move right" and Y stands for "move up". The following diagrams show the case n = 4:

- Cn is the number of different ways a convex polygon with n + 2 sides can be cut into triangles by connecting vertices with straight lines. The following hexagons illustrate the case n = 4:

- Cn is the number of stack-sortable permutations of {1, ..., n}. A permutation w is called stack-sortable if S(w) = (1, ..., n), where S(w) is defined recursively as follows: write w = unv where n is the largest element in w and u and v are shorter sequences, and set S(w) = S(u)S(v)n, with S being the identity for one-element sequences.

- Cn is the number of ways to tile a stairstep shape of height n with n rectangles. The following figure illustrates the case n = 4:

Solving the Catalan numbers

Recurrence relation for Catalan numbers - [math]\displaystyle{ C_0=1 }[/math], and for [math]\displaystyle{ n\ge1 }[/math],

- [math]\displaystyle{ C_n= \sum_{k=0}^{n-1}C_kC_{n-1-k} }[/math].

- [math]\displaystyle{ C_0=1 }[/math], and for [math]\displaystyle{ n\ge1 }[/math],

Let [math]\displaystyle{ G(x)=\sum_{n\ge 0}C_nx^n }[/math] be the generating function. Then

- [math]\displaystyle{ \begin{align} G(x)^2 &=\sum_{n\ge 0}\sum_{k=0}^{n}C_kC_{n-k}x^n\\ xG(x)^2 &=\sum_{n\ge 0}\sum_{k=0}^{n}C_kC_{n-k}x^{n+1}=\sum_{n\ge 1}\sum_{k=0}^{n-1}C_kC_{n-1-k}x^n. \end{align} }[/math]

Due to the recurrence,

- [math]\displaystyle{ G(x)=\sum_{n\ge 0}C_nx^n=C_0+\sum_{n\ge 1}\sum_{k=0}^{n-1}C_kC_{n-1-k}x^n=1+xG(x)^2 }[/math].

Solving [math]\displaystyle{ xG(x)^2-G(x)+1=0 }[/math], we obtain

- [math]\displaystyle{ G(x)=\frac{1\pm(1-4x)^{1/2}}{2x} }[/math].

Only one of these functions can be the generating function for [math]\displaystyle{ C_n }[/math], and it must satisfy

- [math]\displaystyle{ \lim_{x\rightarrow 0}G(x)=C_0=1 }[/math].

It is easy to check that the correct function is

- [math]\displaystyle{ G(x)=\frac{1-(1-4x)^{1/2}}{2x} }[/math].

Expanding [math]\displaystyle{ (1-4x)^{1/2} }[/math] by Newton's formula,

- [math]\displaystyle{ \begin{align} (1-4x)^{1/2} &= \sum_{n\ge 0}{1/2\choose n}(-4x)^n\\ &= 1+\sum_{n\ge 1}{1/2\choose n}(-4x)^n\\ &= 1-4x\sum_{n\ge 0}{1/2\choose n+1}(-4x)^n \end{align} }[/math]

Then, we have

- [math]\displaystyle{ \begin{align} G(x) &= \frac{1-(1-4x)^{1/2}}{2x}\\ &= 2\sum_{n\ge 0}{1/2\choose n+1}(-4x)^n \end{align} }[/math]

Thus,

- [math]\displaystyle{ \begin{align} C_n &=2{1/2\choose n+1}(-4)^n\\ &=2\cdot\left(\frac{1}{2}\cdot\frac{-1}{2}\cdot\frac{-3}{2}\cdots\frac{-(2n-1)}{2}\right)\cdot\frac{1}{(n+1)!}\cdot(-4)^n\\ &=\frac{2^n}{(n+1)!}\prod_{k=1}^n(2k-1)\\ &=\frac{2^n}{(n+1)!}\prod_{k=1}^n\frac{(2k-1)2k}{2k}\\ &=\frac{1}{n!(n+1)!}\prod_{k=1}^n (2k-1)2k\\ &=\frac{(2n)!}{n!(n+1)!}\\ &=\frac{1}{n+1}{2n\choose n}. \end{align} }[/math]

So we prove the following closed form for Catalan number.

Theorem - [math]\displaystyle{ C_n=\frac{1}{n+1}{2n\choose n} }[/math].

Reference

- Graham, Knuth, and Patashnik, Concrete Mathematics: A Foundation for Computer Science, Chapter 7.

- Cameron, Combinatorics: Topics, Techniques, Algorithms, Chapter 4.

- van Lin and Wilson, A course in combinatorics, Chapter 14.