随机算法 (Spring 2013)/Chernoff Bound: Difference between revisions

imported>Etone No edit summary |

imported>Etone |

||

| Line 154: | Line 154: | ||

}} | }} | ||

= Balls into bins, revisited = | == Balls into bins, revisited == | ||

Throwing <math>m</math> balls uniformly and independently to <math>n</math> bins, what is the maximum load of all bins with high probability? In the last class, we gave an analysis of this problem by using a counting argument. | Throwing <math>m</math> balls uniformly and independently to <math>n</math> bins, what is the maximum load of all bins with high probability? In the last class, we gave an analysis of this problem by using a counting argument. | ||

| Line 176: | Line 176: | ||

</math> | </math> | ||

== When <math>m=n</math> == | === When <math>m=n</math> === | ||

When <math>m=n</math>, <math>\mu=1</math>. Write <math>c=1+\delta</math>. The above bound can be written as | When <math>m=n</math>, <math>\mu=1</math>. Write <math>c=1+\delta</math>. The above bound can be written as | ||

| Line 208: | Line 208: | ||

Therefore, for <math>m=n</math>, with high probability, the maximum load is <math>O\left(\frac{e\ln n}{\ln\ln n}\right)</math>. | Therefore, for <math>m=n</math>, with high probability, the maximum load is <math>O\left(\frac{e\ln n}{\ln\ln n}\right)</math>. | ||

== For larger <math>m</math> == | === For larger <math>m</math> === | ||

When <math>m\ge n\ln n</math>, then according to <math>(*)</math>, <math>\mu=\frac{m}{n}\ge \ln n</math> | When <math>m\ge n\ln n</math>, then according to <math>(*)</math>, <math>\mu=\frac{m}{n}\ge \ln n</math> | ||

Latest revision as of 07:47, 24 March 2014

The Chernoff Bound

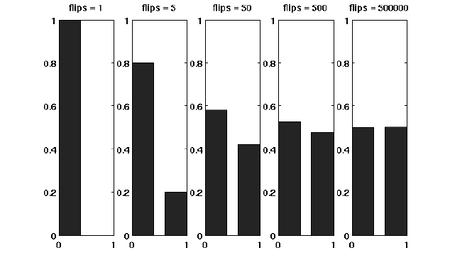

Suppose that we have a fair coin. If we toss it once, then the outcome is completely unpredictable. But if we toss it, say for 1000 times, then the number of HEADs is very likely to be around 500. This striking phenomenon, illustrated in the right figure, is called the concentration. The Chernoff bound captures the concentration of independent trials.

The Chernoff bound is also a tail bound for the sum of independent random variables which may give us exponentially sharp bounds.

Before proving the Chernoff bound, we should talk about the moment generating functions.

Moment generating functions

The more we know about the moments of a random variable [math]\displaystyle{ X }[/math], the more information we would have about [math]\displaystyle{ X }[/math]. There is a so-called moment generating function, which "packs" all the information about the moments of [math]\displaystyle{ X }[/math] into one function.

Definition - The moment generating function of a random variable [math]\displaystyle{ X }[/math] is defined as [math]\displaystyle{ \mathbf{E}\left[\mathrm{e}^{\lambda X}\right] }[/math] where [math]\displaystyle{ \lambda }[/math] is the parameter of the function.

By Taylor's expansion and the linearity of expectations,

- [math]\displaystyle{ \begin{align} \mathbf{E}\left[\mathrm{e}^{\lambda X}\right] &= \mathbf{E}\left[\sum_{k=0}^\infty\frac{\lambda^k}{k!}X^k\right]\\ &=\sum_{k=0}^\infty\frac{\lambda^k}{k!}\mathbf{E}\left[X^k\right] \end{align} }[/math]

The moment generating function [math]\displaystyle{ \mathbf{E}\left[\mathrm{e}^{\lambda X}\right] }[/math] is a function of [math]\displaystyle{ \lambda }[/math].

The Chernoff bound

The Chernoff bounds are exponentially sharp tail inequalities for the sum of independent trials. The bounds are obtained by applying Markov's inequality to the moment generating function of the sum of independent trials, with some appropriate choice of the parameter [math]\displaystyle{ \lambda }[/math].

Chernoff bound (the upper tail) - Let [math]\displaystyle{ X=\sum_{i=1}^n X_i }[/math], where [math]\displaystyle{ X_1, X_2, \ldots, X_n }[/math] are independent Poisson trials. Let [math]\displaystyle{ \mu=\mathbf{E}[X] }[/math].

- Then for any [math]\displaystyle{ \delta\gt 0 }[/math],

- [math]\displaystyle{ \Pr[X\ge (1+\delta)\mu]\le\left(\frac{e^{\delta}}{(1+\delta)^{(1+\delta)}}\right)^{\mu}. }[/math]

Proof. For any [math]\displaystyle{ \lambda\gt 0 }[/math], [math]\displaystyle{ X\ge (1+\delta)\mu }[/math] is equivalent to that [math]\displaystyle{ e^{\lambda X}\ge e^{\lambda (1+\delta)\mu} }[/math], thus - [math]\displaystyle{ \begin{align} \Pr[X\ge (1+\delta)\mu] &= \Pr\left[e^{\lambda X}\ge e^{\lambda (1+\delta)\mu}\right]\\ &\le \frac{\mathbf{E}\left[e^{\lambda X}\right]}{e^{\lambda (1+\delta)\mu}}, \end{align} }[/math]

where the last step follows by Markov's inequality.

Computing the moment generating function [math]\displaystyle{ \mathbf{E}[e^{\lambda X}] }[/math]:

- [math]\displaystyle{ \begin{align} \mathbf{E}\left[e^{\lambda X}\right] &= \mathbf{E}\left[e^{\lambda \sum_{i=1}^n X_i}\right]\\ &= \mathbf{E}\left[\prod_{i=1}^n e^{\lambda X_i}\right]\\ &= \prod_{i=1}^n \mathbf{E}\left[e^{\lambda X_i}\right]. & (\mbox{for independent random variables}) \end{align} }[/math]

Let [math]\displaystyle{ p_i=\Pr[X_i=1] }[/math] for [math]\displaystyle{ i=1,2,\ldots,n }[/math]. Then,

- [math]\displaystyle{ \mu=\mathbf{E}[X]=\mathbf{E}\left[\sum_{i=1}^n X_i\right]=\sum_{i=1}^n\mathbf{E}[X_i]=\sum_{i=1}^n p_i }[/math].

We bound the moment generating function for each individual [math]\displaystyle{ X_i }[/math] as follows.

- [math]\displaystyle{ \begin{align} \mathbf{E}\left[e^{\lambda X_i}\right] &= p_i\cdot e^{\lambda\cdot 1}+(1-p_i)\cdot e^{\lambda\cdot 0}\\ &= 1+p_i(e^\lambda -1)\\ &\le e^{p_i(e^\lambda-1)}, \end{align} }[/math]

where in the last step we apply the Taylor's expansion so that [math]\displaystyle{ e^y\ge 1+y }[/math] where [math]\displaystyle{ y=p_i(e^\lambda-1)\ge 0 }[/math]. (By doing this, we can transform the product to the sum of [math]\displaystyle{ p_i }[/math], which is [math]\displaystyle{ \mu }[/math].)

Therefore,

- [math]\displaystyle{ \begin{align} \mathbf{E}\left[e^{\lambda X}\right] &= \prod_{i=1}^n \mathbf{E}\left[e^{\lambda X_i}\right]\\ &\le \prod_{i=1}^n e^{p_i(e^\lambda-1)}\\ &= \exp\left(\sum_{i=1}^n p_i(e^{\lambda}-1)\right)\\ &= e^{(e^\lambda-1)\mu}. \end{align} }[/math]

Thus, we have shown that for any [math]\displaystyle{ \lambda\gt 0 }[/math],

- [math]\displaystyle{ \begin{align} \Pr[X\ge (1+\delta)\mu] &\le \frac{\mathbf{E}\left[e^{\lambda X}\right]}{e^{\lambda (1+\delta)\mu}}\\ &\le \frac{e^{(e^\lambda-1)\mu}}{e^{\lambda (1+\delta)\mu}}\\ &= \left(\frac{e^{(e^\lambda-1)}}{e^{\lambda (1+\delta)}}\right)^\mu \end{align} }[/math].

For any [math]\displaystyle{ \delta\gt 0 }[/math], we can let [math]\displaystyle{ \lambda=\ln(1+\delta)\gt 0 }[/math] to get

- [math]\displaystyle{ \Pr[X\ge (1+\delta)\mu]\le\left(\frac{e^{\delta}}{(1+\delta)^{(1+\delta)}}\right)^{\mu}. }[/math]

- [math]\displaystyle{ \square }[/math]

The idea of the proof is actually quite clear: we apply Markov's inequality to [math]\displaystyle{ e^{\lambda X} }[/math] and for the rest, we just estimate the moment generating function [math]\displaystyle{ \mathbf{E}[e^{\lambda X}] }[/math]. To make the bound as tight as possible, we minimized the [math]\displaystyle{ \frac{e^{(e^\lambda-1)}}{e^{\lambda (1+\delta)}} }[/math] by setting [math]\displaystyle{ \lambda=\ln(1+\delta) }[/math], which can be justified by taking derivatives of [math]\displaystyle{ \frac{e^{(e^\lambda-1)}}{e^{\lambda (1+\delta)}} }[/math].

We then proceed to the lower tail, the probability that the random variable deviates below the mean value:

Chernoff bound (the lower tail) - Let [math]\displaystyle{ X=\sum_{i=1}^n X_i }[/math], where [math]\displaystyle{ X_1, X_2, \ldots, X_n }[/math] are independent Poisson trials. Let [math]\displaystyle{ \mu=\mathbf{E}[X] }[/math].

- Then for any [math]\displaystyle{ 0\lt \delta\lt 1 }[/math],

- [math]\displaystyle{ \Pr[X\le (1-\delta)\mu]\le\left(\frac{e^{-\delta}}{(1-\delta)^{(1-\delta)}}\right)^{\mu}. }[/math]

Proof. For any [math]\displaystyle{ \lambda\lt 0 }[/math], by the same analysis as in the upper tail version, - [math]\displaystyle{ \begin{align} \Pr[X\le (1-\delta)\mu] &= \Pr\left[e^{\lambda X}\ge e^{\lambda (1-\delta)\mu}\right]\\ &\le \frac{\mathbf{E}\left[e^{\lambda X}\right]}{e^{\lambda (1-\delta)\mu}}\\ &\le \left(\frac{e^{(e^\lambda-1)}}{e^{\lambda (1-\delta)}}\right)^\mu. \end{align} }[/math]

For any [math]\displaystyle{ 0\lt \delta\lt 1 }[/math], we can let [math]\displaystyle{ \lambda=\ln(1-\delta)\lt 0 }[/math] to get

- [math]\displaystyle{ \Pr[X\ge (1-\delta)\mu]\le\left(\frac{e^{-\delta}}{(1-\delta)^{(1-\delta)}}\right)^{\mu}. }[/math]

- [math]\displaystyle{ \square }[/math]

Some useful special forms of the bounds can be derived directly from the above general forms of the bounds. We now know better why we say that the bounds are exponentially sharp.

Useful forms of the Chernoff bound - Let [math]\displaystyle{ X=\sum_{i=1}^n X_i }[/math], where [math]\displaystyle{ X_1, X_2, \ldots, X_n }[/math] are independent Poisson trials. Let [math]\displaystyle{ \mu=\mathbf{E}[X] }[/math]. Then

- 1. for [math]\displaystyle{ 0\lt \delta\le 1 }[/math],

- [math]\displaystyle{ \Pr[X\ge (1+\delta)\mu]\lt \exp\left(-\frac{\mu\delta^2}{3}\right); }[/math]

- [math]\displaystyle{ \Pr[X\le (1-\delta)\mu]\lt \exp\left(-\frac{\mu\delta^2}{2}\right); }[/math]

- 2. for [math]\displaystyle{ t\ge 2e\mu }[/math],

- [math]\displaystyle{ \Pr[X\ge t]\le 2^{-t}. }[/math]

Proof. To obtain the bounds in (1), we need to show that for [math]\displaystyle{ 0\lt \delta\lt 1 }[/math], [math]\displaystyle{ \frac{e^{\delta}}{(1+\delta)^{(1+\delta)}}\le e^{-\delta^2/3} }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ \frac{e^{-\delta}}{(1-\delta)^{(1-\delta)}}\le e^{-\delta^2/2} }[/math]. We can verify both inequalities by standard analysis techniques. To obtain the bound in (2), let [math]\displaystyle{ t=(1+\delta)\mu }[/math]. Then [math]\displaystyle{ \delta=t/\mu-1\ge 2e-1 }[/math]. Hence,

- [math]\displaystyle{ \begin{align} \Pr[X\ge(1+\delta)\mu] &\le \left(\frac{e^\delta}{(1+\delta)^{(1+\delta)}}\right)^\mu\\ &\le \left(\frac{e}{1+\delta}\right)^{(1+\delta)\mu}\\ &\le \left(\frac{e}{2e}\right)^t\\ &\le 2^{-t} \end{align} }[/math]

- [math]\displaystyle{ \square }[/math]

Balls into bins, revisited

Throwing [math]\displaystyle{ m }[/math] balls uniformly and independently to [math]\displaystyle{ n }[/math] bins, what is the maximum load of all bins with high probability? In the last class, we gave an analysis of this problem by using a counting argument.

Now we give a more "advanced" analysis by using Chernoff bounds.

For any [math]\displaystyle{ i\in[n] }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ j\in[m] }[/math], let [math]\displaystyle{ X_{ij} }[/math] be the indicator variable for the event that ball [math]\displaystyle{ j }[/math] is thrown to bin [math]\displaystyle{ i }[/math]. Obviously

- [math]\displaystyle{ \mathbf{E}[X_{ij}]=\Pr[\mbox{ball }j\mbox{ is thrown to bin }i]=\frac{1}{n} }[/math]

Let [math]\displaystyle{ Y_i=\sum_{j\in[m]}X_{ij} }[/math] be the load of bin [math]\displaystyle{ i }[/math].

Then the expected load of bin [math]\displaystyle{ i }[/math] is

[math]\displaystyle{ (*)\qquad \mu=\mathbf{E}[Y_i]=\mathbf{E}\left[\sum_{j\in[m]}X_{ij}\right]=\sum_{j\in[m]}\mathbf{E}[X_{ij}]=m/n. }[/math]

For the case [math]\displaystyle{ m=n }[/math], it holds that [math]\displaystyle{ \mu=1 }[/math]

Note that [math]\displaystyle{ Y_i }[/math] is a sum of [math]\displaystyle{ m }[/math] mutually independent indicator variable. Applying Chernoff bound, for any particular bin [math]\displaystyle{ i\in[n] }[/math],

- [math]\displaystyle{ \Pr[Y_i\gt (1+\delta)\mu] \le \left(\frac{e^{\delta}}{(1+\delta)^{1+\delta}}\right)^\mu. }[/math]

When [math]\displaystyle{ m=n }[/math]

When [math]\displaystyle{ m=n }[/math], [math]\displaystyle{ \mu=1 }[/math]. Write [math]\displaystyle{ c=1+\delta }[/math]. The above bound can be written as

- [math]\displaystyle{ \Pr[Y_i\gt c] \le \frac{e^{c-1}}{c^c}. }[/math]

Let [math]\displaystyle{ c=\frac{e\ln n}{\ln\ln n} }[/math], we evaluate [math]\displaystyle{ \frac{e^{c-1}}{c^c} }[/math] by taking logarithm to its reciprocal.

- [math]\displaystyle{ \begin{align} \ln\left(\frac{c^c}{e^{c-1}}\right) &= c\ln c-c+1\\ &= c(\ln c-1)+1\\ &= \frac{e\ln n}{\ln\ln n}\left(\ln\ln n-\ln\ln\ln n\right)+1\\ &\ge \frac{e\ln n}{\ln\ln n}\cdot\frac{2}{e}\ln\ln n+1\\ &\ge 2\ln n. \end{align} }[/math]

Thus,

- [math]\displaystyle{ \Pr\left[Y_i\gt \frac{e\ln n}{\ln\ln n}\right] \le \frac{1}{n^2}. }[/math]

Applying the union bound, the probability that there exists a bin with load [math]\displaystyle{ \gt 12\ln n }[/math] is

- [math]\displaystyle{ n\cdot \Pr\left[Y_1\gt \frac{e\ln n}{\ln\ln n}\right] \le \frac{1}{n} }[/math].

Therefore, for [math]\displaystyle{ m=n }[/math], with high probability, the maximum load is [math]\displaystyle{ O\left(\frac{e\ln n}{\ln\ln n}\right) }[/math].

For larger [math]\displaystyle{ m }[/math]

When [math]\displaystyle{ m\ge n\ln n }[/math], then according to [math]\displaystyle{ (*) }[/math], [math]\displaystyle{ \mu=\frac{m}{n}\ge \ln n }[/math]

We can apply an easier form of the Chernoff bounds,

- [math]\displaystyle{ \Pr[Y_i\ge 2e\mu]\le 2^{-2e\mu}\le 2^{-2e\ln n}\lt \frac{1}{n^2}. }[/math]

By the union bound, the probability that there exists a bin with load [math]\displaystyle{ \ge 2e\frac{m}{n} }[/math] is,

- [math]\displaystyle{ n\cdot \Pr\left[Y_1\gt 2e\frac{m}{n}\right] = n\cdot \Pr\left[Y_1\gt 2e\mu\right]\le \frac{1}{n} }[/math].

Therefore, for [math]\displaystyle{ m\ge n\ln n }[/math], with high probability, the maximum load is [math]\displaystyle{ O\left(\frac{m}{n}\right) }[/math].

Set Balancing

Supposed that we have an [math]\displaystyle{ n\times m }[/math] matrix [math]\displaystyle{ A }[/math] with 0-1 entries. We are looking for a [math]\displaystyle{ b\in\{-1,+1\}^m }[/math] that minimizes [math]\displaystyle{ \|Ab\|_\infty }[/math].

Recall that [math]\displaystyle{ \|\cdot\|_\infty }[/math] is the infinity norm (also called [math]\displaystyle{ L_\infty }[/math] norm) of a vector, and for the vector [math]\displaystyle{ c=Ab }[/math],

- [math]\displaystyle{ \|Ab\|_\infty=\max_{i=1,2,\ldots,n}|c_i| }[/math].

We can also describe this problem as an optimization:

- [math]\displaystyle{ \begin{align} \mbox{minimize } &\quad \|Ab\|_\infty\\ \mbox{subject to: } &\quad b\in\{-1,+1\}^m. \end{align} }[/math]

This problem is called set balancing for a reason.

The problem arises in designing statistical experiments. Suppose that we have [math]\displaystyle{ m }[/math] subjects, each of which may have up to [math]\displaystyle{ n }[/math] features. This gives us an [math]\displaystyle{ n\times m }[/math] matrix [math]\displaystyle{ A }[/math]:

where each column represents a subject and each row represent a feature. An entry [math]\displaystyle{ a_{ij}\in\{0,1\} }[/math] indicates whether subject [math]\displaystyle{ j }[/math] has feature [math]\displaystyle{ i }[/math]. By multiplying a vector [math]\displaystyle{ b\in\{-1,+1\}^m }[/math]

the subjects are partitioned into two disjoint groups: one for -1 and other other for +1. Each [math]\displaystyle{ c_i }[/math] gives the difference between the numbers of subjects with feature [math]\displaystyle{ i }[/math] in the two groups. By minimizing [math]\displaystyle{ \|Ab\|_\infty=\|c\|_\infty }[/math], we ask for an optimal partition so that each feature is roughly as balanced as possible between the two groups. In a scientific experiment, one of the group serves as a control group (对照组). Ideally, we want the two groups are statistically identical, which is usually impossible to achieve in practice. The requirement of minimizing [math]\displaystyle{ \|Ab\|_\infty }[/math] actually means the statistical difference between the two groups are minimized. |

We propose an extremely simple "randomized algorithm" for computing a [math]\displaystyle{ b\in\{-1,+1\}^m }[/math]: for each [math]\displaystyle{ i=1,2,\ldots, m }[/math], let [math]\displaystyle{ b_i }[/math] be independently chosen from [math]\displaystyle{ \{-1,+1\} }[/math], such that

- [math]\displaystyle{ b_i= \begin{cases} -1 & \mbox{with probability }\frac{1}{2}\\ +1 &\mbox{with probability }\frac{1}{2} \end{cases}. }[/math]

This procedure can hardly be called as an "algorithm", because its decision is made disregard of the input [math]\displaystyle{ A }[/math]. We then show that despite of this obliviousness, the algorithm chooses a good enough [math]\displaystyle{ b }[/math], such that for any [math]\displaystyle{ A }[/math], [math]\displaystyle{ \|Ab\|_\infty=O(\sqrt{m\ln n}) }[/math] with high probability.

Theorem - Let [math]\displaystyle{ A }[/math] be an [math]\displaystyle{ n\times m }[/math] matrix with 0-1 entries. For a random vector [math]\displaystyle{ b }[/math] with [math]\displaystyle{ m }[/math] entries chosen independently and with equal probability from [math]\displaystyle{ \{-1,+1\} }[/math],

- [math]\displaystyle{ \Pr[\|Ab\|_\infty\gt 2\sqrt{2m\ln n}]\le\frac{2}{n} }[/math].

- Let [math]\displaystyle{ A }[/math] be an [math]\displaystyle{ n\times m }[/math] matrix with 0-1 entries. For a random vector [math]\displaystyle{ b }[/math] with [math]\displaystyle{ m }[/math] entries chosen independently and with equal probability from [math]\displaystyle{ \{-1,+1\} }[/math],

Proof. Consider particularly the [math]\displaystyle{ i }[/math]-th row of [math]\displaystyle{ A }[/math]. The entry of [math]\displaystyle{ Ab }[/math] contributed by row [math]\displaystyle{ i }[/math] is [math]\displaystyle{ c_i=\sum_{j=1}^m a_{ij}b_j }[/math].

Let [math]\displaystyle{ k }[/math] be the non-zero entries in the row. If [math]\displaystyle{ k\le2\sqrt{2m\ln n} }[/math], then clearly [math]\displaystyle{ |c_i| }[/math] is no greater than [math]\displaystyle{ 2\sqrt{2m\ln n} }[/math]. On the other hand if [math]\displaystyle{ k\gt 2\sqrt{2m\ln n} }[/math] then the [math]\displaystyle{ k }[/math] nonzero terms in the sum

- [math]\displaystyle{ c_i=\sum_{j=1}^m a_{ij}b_j }[/math]

are independent, each with probability 1/2 of being either +1 or -1.

Thus, for these [math]\displaystyle{ k }[/math] nonzero terms, each [math]\displaystyle{ b_i }[/math] is either positive or negative independently with equal probability. There are expectedly [math]\displaystyle{ \mu=\frac{k}{2} }[/math] positive [math]\displaystyle{ b_i }[/math]'s among these [math]\displaystyle{ k }[/math] terms, and [math]\displaystyle{ c_i\lt -2\sqrt{2m\ln n} }[/math] only occurs when there are less than [math]\displaystyle{ \frac{k}{2}-\sqrt{2m\ln n}=\left(1-\delta\right)\mu }[/math] positive [math]\displaystyle{ b_i }[/math]'s, where [math]\displaystyle{ \delta=\frac{2\sqrt{2m\ln n}}{k} }[/math]. Applying Chernoff bound, this event occurs with probability at most

- [math]\displaystyle{ \begin{align} \exp\left(-\frac{\mu\delta^2}{2}\right) &= \exp\left(-\frac{k}{2}\cdot\frac{8m\ln n}{2k^2}\right)\\ &= \exp\left(-\frac{2m\ln n}{k}\right)\\ &\le \exp\left(-\frac{2m\ln n}{m}\right)\\ &\le n^{-2}. \end{align} }[/math]

The same argument can be applied to negative [math]\displaystyle{ b_i }[/math]'s, so that the probability that [math]\displaystyle{ c_i\gt 2\sqrt{2m\ln n} }[/math] is at most [math]\displaystyle{ n^{-2} }[/math]. Therefore, by the union bound,

- [math]\displaystyle{ \Pr[|c_i|\gt 2\sqrt{2m\ln n}]\le\frac{2}{n^2} }[/math].

Apply the union bound to all [math]\displaystyle{ n }[/math] rows.

- [math]\displaystyle{ \Pr[\|Ab\|_\infty\gt 2\sqrt{2m\ln n}]\le n\cdot\Pr[|c_i|\gt 2\sqrt{2m\ln n}]\le\frac{2}{n} }[/math].

- [math]\displaystyle{ \square }[/math]

How good is this randomized algorithm? In fact when [math]\displaystyle{ m=n }[/math] there exists a matrix [math]\displaystyle{ A }[/math] such that [math]\displaystyle{ \|Ab\|_\infty=\Omega(\sqrt{n}) }[/math] for any choice of [math]\displaystyle{ b\in\{-1,+1\}^n }[/math].

Packet Routing

The problem raises from parallel computing. Consider that we have [math]\displaystyle{ N }[/math] processors, connected by a communication network. The processors communicate with each other by sending and receiving packets through the network. We consider the following packet routing problem:

- Every processor is sending a packet to a unique destination. Therefore for [math]\displaystyle{ [N] }[/math] the set of processors, the destinations are given by a permutation [math]\displaystyle{ \pi }[/math] of [math]\displaystyle{ [N] }[/math], such that for every processor [math]\displaystyle{ i\in[N] }[/math], the processor [math]\displaystyle{ i }[/math] is sending a packet to processor [math]\displaystyle{ \pi(i) }[/math].

- The communication is synchronized, such that for each round, every link (an edge of the graph) can forward at most one packet.

With a complete graph as the network. For any permutation [math]\displaystyle{ \pi }[/math] of [math]\displaystyle{ [N] }[/math], all packets can be routed to their destinations in parallel with one round of communication. However, such an ideal connectivity is usually not available in reality, either because they are too expensive, or because they are physically impossible. We are interested in the case the graph is sparse, such that the number of edges is significantly smaller than the complete graph, yet the distance between any pair of vertices is small, so that the packets can be efficiently routed between pairs of vertices.

Routing on a hypercube

A hypercube (sometimes called Boolean cube, Hamming cube, or just cube) is defined over [math]\displaystyle{ N }[/math] nodes, for [math]\displaystyle{ N }[/math] a power of 2. We assume that [math]\displaystyle{ N=2^d }[/math]. A hypercube of [math]\displaystyle{ d }[/math] dimensions, or a [math]\displaystyle{ d }[/math]-cube, is an undirected graph with the vertex set [math]\displaystyle{ \{0,1\}^d }[/math], such that for any [math]\displaystyle{ u,v\in\{0,1\}^d }[/math], [math]\displaystyle{ u }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ v }[/math] are adjacent if and only if [math]\displaystyle{ h(u,v)=1 }[/math], where [math]\displaystyle{ h(u,v) }[/math] is the Hamming distance between [math]\displaystyle{ u }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ v }[/math].

A [math]\displaystyle{ d }[/math]-cube is a [math]\displaystyle{ d }[/math]-degree regular graph over [math]\displaystyle{ N=2^d }[/math] vertices. For any pair [math]\displaystyle{ (u,v) }[/math] of vertices, the distance between [math]\displaystyle{ u }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ v }[/math] is at most [math]\displaystyle{ d }[/math]. (How do we know this? Since it takes at most [math]\displaystyle{ d }[/math] steps to fix any binary string of length [math]\displaystyle{ d }[/math] bit-by-bit to any other.) This directly gives us the following very natural routing algorithm.

Bit-Fixing Routing Algorithm For each packet:

- Let [math]\displaystyle{ u, v\in\{0,1\}^d }[/math] be the origin and destination of the packet respectively.

- For [math]\displaystyle{ i=1 }[/math] to [math]\displaystyle{ d }[/math], do:

- if [math]\displaystyle{ u_i\neq v_i }[/math] then traverse the edge [math]\displaystyle{ (v_1,\ldots,v_{i-1},u_i,\ldots,u_d)\rightarrow (v_1,\ldots,v_{i-1},v_i,u_{i+1}\ldots,u_d) }[/math].

- Oblivious routing algorithms

- This algorithm is blessed with a desirable property: at each routing step, the choice of link depends only on the the current node and the destination. We call the algorithms with this property oblivious routing algorithms. (Actually, the standard definition of obliviousness allows the choice also depends on the origin. The bit-fixing algorithm is even more oblivious than this standard definition.) Compared to the routing algorithms which are adaptive to the path that the packet traversed, oblivious routing is more simple thus can be implemented by smaller routing table (or simple devices called switches).

- Queuing policies

- When routing [math]\displaystyle{ N }[/math] packets in parallel, it is possible that more than one packets want to use the same edge at the same time. We assume that a queue is associated to each edge, such that the packets to be delivered through an edge are put into the queue associated with the edge. With some queuing policy (e.g. FIFO, or furthest to do), the queued packets are delivered through the edge by at most one packet per each round.

For the bit-fixing routing algorithm defined above, regardless of the queuing policy, there always exists a bad permutation [math]\displaystyle{ \pi }[/math] which specifies the destinations, such that it takes [math]\displaystyle{ \Omega(\sqrt{N}) }[/math] steps by the bit-fixing algorithm to route all [math]\displaystyle{ N }[/math] packets to their destinations. (You can prove this by yourself.)

This is pretty bad, because we expect that the routing time is comparable to the diameter of the network, which is only [math]\displaystyle{ d=\log N }[/math] for hypercube.

The lower bound actually applies generally for any deterministic oblivious routing algorithms:

Theorem [Kaklamanis, Krizanc, Tsantilas, 1991] - In any [math]\displaystyle{ N }[/math]-node communication network with maximum degree [math]\displaystyle{ d }[/math], any deterministic oblivious algorithm for routing an arbitrary permutation requires [math]\displaystyle{ \Omega(\sqrt{N}/d) }[/math] parallel communication steps in the worst case.

The proof of the lower bound is rather technical and complicated. However, the intuition is quite clear: for any oblivious rule for routing, there always exists a permutation which causes a very high congestion, such that many packets have to be delivered through the same edge, thus no matter what queuing policy is used, the maximum delay must be very high.

Average-case analysis for independent destinations

We analyze the average-case performance of the bit-fixing routing algorithm. We relax the problem to non-permutation destinations. That is, instead of restricting that every processor has a distinct destination, we now allow each processor choose an arbitrary destination in [math]\displaystyle{ \{0,1\}^d }[/math].

For the average case, for each node [math]\displaystyle{ v\in\{0,1\}^d }[/math], its destination is a uniformly and independently random node from [math]\displaystyle{ \{0,1\}^d }[/math].

For each node [math]\displaystyle{ v\in\{0,1\}^d }[/math], let [math]\displaystyle{ P_v }[/math] denote the route for [math]\displaystyle{ v }[/math] to its random destination [math]\displaystyle{ r }[/math]. [math]\displaystyle{ P_v }[/math] is a sequence of edges along the bit-fixing route from [math]\displaystyle{ v }[/math] to [math]\displaystyle{ r }[/math].

Reduce the delay of a route to the number of packets that pass through the route

We consider the delay incurred by each node, which is the total time that its packet is waiting in the queue. The total running time of the algorithm is bounded by the maximum delay plus [math]\displaystyle{ d }[/math].

We assume that the queueing policy satisfies a very natural requirement:

- Natural queuing assumption

- If a queue is not empty at the beginning of a time step, some packet is sent along the edge associated with that queue during that time step.

Lemma 2.1 - With the above assumption of the queuing policy, the delay inccured by [math]\displaystyle{ u }[/math] is at most the number of packets whose routes pass through at least one edge in [math]\displaystyle{ P_u }[/math].

Proof. See Lemma 4.5 in the textbook [MR].

- [math]\displaystyle{ \square }[/math]

Represent the delay as the sum of independent trials

Let the random variable [math]\displaystyle{ H_{uv} }[/math] indicate whether [math]\displaystyle{ P_u }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ P_v }[/math] share at least one edge. That is,

- [math]\displaystyle{ H_{uv} = \begin{cases} 1 & \text{if }P_u\text{ and }P_v\text{ share at least one edge},\\ 0 & \text{otherwise}. \end{cases} }[/math]

Fix a node [math]\displaystyle{ u\in\{0,1\}^d }[/math] and the corresponding route [math]\displaystyle{ P_u }[/math]. The random variable [math]\displaystyle{ H_u=\sum_{v\in\{0,1\}^d}H_{uv} }[/math] gives the total number of packets whose routes pass through [math]\displaystyle{ P_u }[/math]. Due to Lemma 2.1, [math]\displaystyle{ H_u }[/math] gives an upper bound on the delay inccured by [math]\displaystyle{ u }[/math].

We will then bound [math]\displaystyle{ H_u }[/math]. Note that for [math]\displaystyle{ v\neq u }[/math], [math]\displaystyle{ H_{uv} }[/math] are independent trials (because the destinations of [math]\displaystyle{ u }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ v }[/math] are independent), thus we can apply the Chernoff bound. To do so, we must estimate the expectation [math]\displaystyle{ \mathbf{E}[H_u] }[/math].

Estimate the expectation of the sum

For any edge [math]\displaystyle{ e }[/math] in the hypercube, let the random variable [math]\displaystyle{ T(e) }[/math] denote the number of routes that pass through [math]\displaystyle{ e }[/math]. As we argued above that [math]\displaystyle{ H_u }[/math] is the number of packets that pass though the route [math]\displaystyle{ P_u }[/math], then obviously

- [math]\displaystyle{ H_u\le \sum_{e\in P_u}T(e), }[/math]

where we abuse the notation [math]\displaystyle{ e\in P_u }[/math] to denote the edge [math]\displaystyle{ e }[/math] appeared in the route [math]\displaystyle{ P_u }[/math].

Therefore,

- [math]\displaystyle{ \mathbf{E}[H_u]\le\sum_{e\in P_u}\mathbf{E}[T(e)].\qquad\qquad(*) }[/math]

For every node [math]\displaystyle{ v\in\{0,1\}^d }[/math], the length of the route [math]\displaystyle{ P_v }[/math], denoted [math]\displaystyle{ |P_v| }[/math], is the number of different bits between [math]\displaystyle{ v }[/math] and the last node in the route (because of the "bit-fixing"). For the uniformly random destination, [math]\displaystyle{ \mathbf{E}[|P_v|]=d/2 }[/math] (a random node in [math]\displaystyle{ \{0,1\}^d }[/math] expectedly flips [math]\displaystyle{ d/2 }[/math] bits in any fixed [math]\displaystyle{ v\in\{0,1\}^d }[/math]). Thus,

- [math]\displaystyle{ \sum_{v\in\{0,1\}^d}\mathbf{E}[|P_v|]=\frac{dN}{2}. }[/math]

It is obvious that we can count the sum of lengths of a set of routes by accumulating their passes through edges, that is

- [math]\displaystyle{ \sum_{v\in\{0,1\}^d}|P_v|=\sum_{e}T(e), }[/math]

Therefore,

- [math]\displaystyle{ \sum_{e}\mathbf{E}[T(e)] =\sum_{v\in\{0,1\}^d}\mathbf{E}[|P_v|]=\frac{dN}{2}, }[/math]

where the sum [math]\displaystyle{ \sum_{e}\mathbf{E}[T(e)] }[/math] is taken over all edges in the hypercube.

An important observation is that the distribution of [math]\displaystyle{ T(e) }[/math]'s are all symmetric, thus all [math]\displaystyle{ \mathbf{E}[T(e)] }[/math]'s are equal. The number of edges in the hypercube is [math]\displaystyle{ \frac{dN}{2} }[/math]. Therefore, for every edge [math]\displaystyle{ e }[/math] in the hupercube,

- [math]\displaystyle{ \mathbf{E}[T(e)]=\frac{2}{dN}\cdot\frac{dN}{2}=1. }[/math]

The length of [math]\displaystyle{ P_u }[/math] is at most [math]\displaystyle{ d }[/math]. Due to [math]\displaystyle{ (*) }[/math], the expectation of [math]\displaystyle{ H_u }[/math] is [math]\displaystyle{ \mathbf{E}[H_u]\le\sum_{e\in P_u}\mathbf{E}[T(e)]\le d }[/math].

Apply the Chernoff bound

We apply the following form of the Chernoff bound:

Chernoff bound - Let [math]\displaystyle{ X=\sum_{i=1}^n X_i }[/math], where [math]\displaystyle{ X_1, X_2, \ldots, X_n }[/math] are independent Poisson trials. Let [math]\displaystyle{ \mu=\mathbf{E}[X] }[/math]. Then for [math]\displaystyle{ t\ge 2e\mu }[/math],

- [math]\displaystyle{ \Pr[X\ge t]\le 2^{-t}. }[/math]

- Let [math]\displaystyle{ X=\sum_{i=1}^n X_i }[/math], where [math]\displaystyle{ X_1, X_2, \ldots, X_n }[/math] are independent Poisson trials. Let [math]\displaystyle{ \mu=\mathbf{E}[X] }[/math]. Then for [math]\displaystyle{ t\ge 2e\mu }[/math],

It holds that [math]\displaystyle{ 6d\gt 2e\mathbf{E}[H_u]=2ed }[/math]. By applying the Chernoff bound,

- [math]\displaystyle{ \Pr[H_u\gt 6d]\lt 2^{-6d} }[/math].

Note that [math]\displaystyle{ H_u }[/math] only gives the bound on the delay incurred by a particular node [math]\displaystyle{ u }[/math]. By the union bound,

- [math]\displaystyle{ \begin{align} \Pr[\text{the maximum delay of Phase I}\gt 6d] &\le \Pr[\max_{u\in\{0,1\}^d}H_u\gt 6d]\\ &\le N\Pr[H_u\gt 6d]\\ &\lt N\cdot 2^{-6d}\\ &=2^{-5d}. \end{align} }[/math]

The running time is the maximum delay plus the length of a route, thus is [math]\displaystyle{ \gt 7d }[/math] with probability [math]\displaystyle{ \lt 2^{-5d} }[/math].

A two-phase randomized routing algorithm

The above analysis of the performance of bit-fixing for independent random destinations hints us that we can first route the packets to random "relay"s to avoid the high congestion. This was first discovered by Leslie Valiant who uses the idea to give a simple and elegant randomized routing algorithm for permutation routing.

The algorithm works in two phases.

Two-Phase Routing Algorithm For each packet:

Phase I: Route the packet to a random destination using the bit-fixing algorithm.

Phase II: Route the packet from the random location to its final destination using the bit-fixing algorithm.

It looks counter-intuitive that first routing the packets to irrelevant intermediate nodes actually improves the overall performance.

To simplify the analysis, we assume that no packet is sent in Phase II before all packets have finished Phase I.

Phase I is exactly the bit-fixing routing for uniformly and independently random destinations, which as we analyzed in the last section, has a running time within [math]\displaystyle{ 7d }[/math] for probability at least [math]\displaystyle{ 1-2^{-5d} }[/math].

The Phase II is a "backward" running of Phase I. All the analysis of Phase I can be directly applied to Phase II. Thus, the running time of Phase II is [math]\displaystyle{ \gt 7d }[/math] with probability [math]\displaystyle{ \lt 2^{-5d} }[/math]. By the union bound, the total running time of the randomized routing algorithm is no more than [math]\displaystyle{ 14d=O(\log N) }[/math] with high probability.