组合数学 (Spring 2013)/Existence problems: Difference between revisions

imported>Etone |

imported>Etone |

||

| Line 69: | Line 69: | ||

In 1928 young Emanuel Sperner gave a combinatorial proof of the famous Brouwer's fixed point theorem by proving the following lemma (now called Sperner's lemma), with an extremely elegant proof. | In 1928 young Emanuel Sperner gave a combinatorial proof of the famous Brouwer's fixed point theorem by proving the following lemma (now called Sperner's lemma), with an extremely elegant proof. | ||

{{Theorem|Sperner's Lemma (1928)| | {{Theorem|Sperner's Lemma (1928)| | ||

: | :For any properly colored triangulation, there exists a cell receiving all three colors. | ||

}} | }} | ||

{{Proof| | {{Proof| | ||

Revision as of 14:30, 18 April 2013

Existence by Counting

Shannon's circuit lower bound

This is a fundamental problem in in Computer Science.

A boolean function is a function in the form [math]\displaystyle{ f:\{0,1\}^n\rightarrow \{0,1\} }[/math].

Boolean circuit is a mathematical model of computation. Formally, a boolean circuit is a directed acyclic graph. Nodes with indegree zero are input nodes, labeled [math]\displaystyle{ x_1, x_2, \ldots , x_n }[/math]. A circuit has a unique node with outdegree zero, called the output node. Every other node is a gate. There are three types of gates: AND, OR (both with indegree two), and NOT (with indegree one).

Computations in Turing machines can be simulated by circuits, and any boolean function in P can be computed by a circuit with polynomially many gates. Thus, if we can find a function in NP that cannot be computed by any circuit with polynomially many gates, then NP[math]\displaystyle{ \neq }[/math]P.

The following theorem due to Shannon says that functions with exponentially large circuit complexity do exist.

Theorem (Shannon 1949) - There is a boolean function [math]\displaystyle{ f:\{0,1\}^n\rightarrow \{0,1\} }[/math] with circuit complexity greater than [math]\displaystyle{ \frac{2^n}{3n} }[/math].

Proof. We first count the number of boolean functions [math]\displaystyle{ f:\{0,1\}^n\rightarrow \{0,1\} }[/math]. There are [math]\displaystyle{ 2^{2^n} }[/math] boolean functions [math]\displaystyle{ f:\{0,1\}^n\rightarrow \{0,1\} }[/math].

Then we count the number of boolean circuit with fixed number of gates. Fix an integer [math]\displaystyle{ t }[/math], we count the number of circuits with [math]\displaystyle{ t }[/math] gates. By the De Morgan's laws, we can assume that all NOTs are pushed back to the inputs. Each gate has one of the two types (AND or OR), and has two inputs. Each of the inputs to a gate is either a constant 0 or 1, an input variable [math]\displaystyle{ x_i }[/math], an inverted input variable [math]\displaystyle{ \neg x_i }[/math], or the output of another gate; thus, there are at most [math]\displaystyle{ 2+2n+t-1 }[/math] possible gate inputs. It follows that the number of circuits with [math]\displaystyle{ t }[/math] gates is at most [math]\displaystyle{ 2^t(t+2n+1)^{2t} }[/math].

If [math]\displaystyle{ t=2^n/3n }[/math], then

- [math]\displaystyle{ \frac{2^t(t+2n+1)^{2t}}{2^{2^n}}=o(1)\lt 1, }[/math] thus, [math]\displaystyle{ 2^t(t+2n+1)^{2t} \lt 2^{2^n}. }[/math]

Each boolean circuit computes one boolean function. Therefore, there must exist a boolean function [math]\displaystyle{ f }[/math] which cannot be computed by any circuits with [math]\displaystyle{ 2^n/3n }[/math] gates.

- [math]\displaystyle{ \square }[/math]

Note that by Shannon's theorem, not only there exists a boolean function with exponentially large circuit complexity, but almost all boolean functions have exponentially large circuit complexity.

Double counting

The double counting principle states the following obvious fact: if the elements of a set are counted in two different ways, the answers are the same.

Handshaking lemma

The following lemma is a standard demonstration of double counting.

Handshaking Lemma - At a party, the number of guests who shake hands an odd number of times is even.

We model this scenario as an undirected graph [math]\displaystyle{ G(V,E) }[/math] with [math]\displaystyle{ |V|=n }[/math] standing for the [math]\displaystyle{ n }[/math] guests. There is an edge [math]\displaystyle{ uv\in E }[/math] if [math]\displaystyle{ u }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ v }[/math] shake hands. Let [math]\displaystyle{ d(v) }[/math] be the degree of vertex [math]\displaystyle{ v }[/math], which represents the number of times that [math]\displaystyle{ v }[/math] shakes hand. The handshaking lemma states that in any undirected graph, the number of vertices whose degrees are odd is even. It is sufficient to show that the sum of odd degrees is even.

The handshaking lemma is a direct consequence of the following lemma, which is proved by Euler in his 1736 paper on Seven Bridges of Königsberg that began the study of graph theory.

Lemma (Euler 1736) - [math]\displaystyle{ \sum_{v\in V}d(v)=2|E| }[/math]

Proof. We count the number of directed edges. A directed edge is an ordered pair [math]\displaystyle{ (u,v) }[/math] such that [math]\displaystyle{ \{u,v\}\in E }[/math]. There are two ways to count the directed edges.

First, we can enumerate by edges. Pick every edge [math]\displaystyle{ uv\in E }[/math] and apply two directions [math]\displaystyle{ (u,v) }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ (v,u) }[/math] to the edge. This gives us [math]\displaystyle{ 2|E| }[/math] directed edges.

On the other hand, we can enumerate by vertices. Pick every vertex [math]\displaystyle{ v\in V }[/math] and for each of its [math]\displaystyle{ d(v) }[/math] neighbors, say [math]\displaystyle{ u }[/math], generate a directed edge [math]\displaystyle{ (v,u) }[/math]. This gives us [math]\displaystyle{ \sum_{v\in V}d(v) }[/math] directed edges.

It is obvious that the two terms are equal, since we just count the same thing twice with different methods. The lemma follows.

- [math]\displaystyle{ \square }[/math]

The handshaking lemma is implied directly by the above lemma, since the sum of even degrees is even.

Sperner's lemma

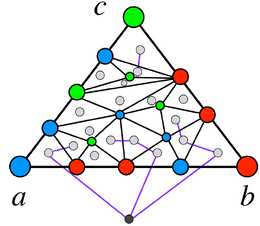

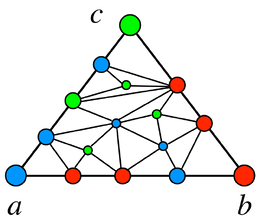

A triangulation of a triangle [math]\displaystyle{ abc }[/math] is a decomposition of [math]\displaystyle{ abc }[/math] to small triangles (called cells), such that any two different cells are either disjoint, or share an edge, or a vertex.

A proper coloring of a triangulation of triangle [math]\displaystyle{ abc }[/math] is a coloring of all vertices in the triangulation with three colors: red, blue, and green, such that the following constraints are satisfied:

- The three vertices [math]\displaystyle{ a,b }[/math], and [math]\displaystyle{ c }[/math] of the big triangle receive all three colors.

- The vertices in each of the three lines [math]\displaystyle{ ab }[/math], [math]\displaystyle{ bc }[/math], and [math]\displaystyle{ ac }[/math] receive two colors.

The following figure is an example of a properly colored triangulation.

In 1928 young Emanuel Sperner gave a combinatorial proof of the famous Brouwer's fixed point theorem by proving the following lemma (now called Sperner's lemma), with an extremely elegant proof.

Sperner's Lemma (1928) - For any properly colored triangulation, there exists a cell receiving all three colors.

The Pigeonhole Principle

The pigeonhole principle states the following "obvious" fact:

- [math]\displaystyle{ n+1 }[/math] pigeons cannot sit in [math]\displaystyle{ n }[/math] holes so that every pigeon is alone in its hole.

This is one of the oldest non-constructive principles: it states only the existence of a pigeonhole with more than one pigeons and says nothing about how to find such a pigeonhole.

The general form of pigeonhole principle, also known as the averaging principle, is stated as follows.

Generalized pigeonhole principle - If a set consisting of more than [math]\displaystyle{ mn }[/math] objects is partitioned into [math]\displaystyle{ n }[/math] classes, then some class receives more than [math]\displaystyle{ m }[/math] objects.

Inevitable divisors

The following is one of Erdős' favorite initiation questions to mathematics. The proof uses the Pigeonhole Principle.

Theorem - For any subset [math]\displaystyle{ S\subseteq\{1,2,\ldots,2n\} }[/math] of size [math]\displaystyle{ |S|\gt n\, }[/math], there are two numbers [math]\displaystyle{ a,b\in S }[/math] such that [math]\displaystyle{ a|b\, }[/math].

Proof. For every odd number [math]\displaystyle{ m\in\{1,2,\ldots,2n\} }[/math], let

- [math]\displaystyle{ C_m=\{2^km\mid k\ge 0, 2^km\le 2n\} }[/math].

It is easy to see that for any [math]\displaystyle{ b\lt a }[/math] from the same [math]\displaystyle{ C_m }[/math], it holds that [math]\displaystyle{ a|b }[/math].

Every number [math]\displaystyle{ a\in S }[/math] can be uniquely represented as [math]\displaystyle{ a=2^km }[/math] for some odd number [math]\displaystyle{ m }[/math], thus belongs to exactly one of [math]\displaystyle{ C_m }[/math], for odd [math]\displaystyle{ m\in\{1,2,\ldots, 2n\} }[/math]. There are [math]\displaystyle{ n }[/math] odd numbers in [math]\displaystyle{ \{1,2,\ldots,2n\} }[/math], thus [math]\displaystyle{ n }[/math] different [math]\displaystyle{ C_m }[/math], but [math]\displaystyle{ |S|\gt n }[/math], thus there must exist distinct [math]\displaystyle{ a,b\in S }[/math], supposed that [math]\displaystyle{ b\lt a }[/math], belonging to the same [math]\displaystyle{ C_m }[/math], which implies that [math]\displaystyle{ a|b }[/math].

- [math]\displaystyle{ \square }[/math]

Monotonic subsequences

Let [math]\displaystyle{ (a_1,a_2,\ldots,a_n) }[/math] be a sequence of [math]\displaystyle{ n }[/math] distinct real numbers. A subsequence is a sequence of distinct terms of [math]\displaystyle{ (a_1,a_2,\ldots,a_n) }[/math] appearing in the same order in which they appear in [math]\displaystyle{ (a_1,a_2,\ldots,a_n) }[/math]. Formally, a subsequence of [math]\displaystyle{ (a_1,a_2,\ldots,a_n) }[/math] is an [math]\displaystyle{ (a_{i_1},a_{i_2},\ldots,a_{i_k}) }[/math], with [math]\displaystyle{ i_1\lt i_2\lt \cdots\lt i_k }[/math].

A sequence [math]\displaystyle{ (a_1,a_2,\ldots,a_n) }[/math] is increasing if [math]\displaystyle{ a_1\lt a_2\lt \cdots\lt a_n }[/math], and decreasing if [math]\displaystyle{ a_1\gt a_2\gt \cdots\gt a_n }[/math].

We are interested in the longest increasing and decreasing subsequences of an [math]\displaystyle{ a_1\lt a_2\lt \cdots\lt a_n }[/math]. It is intuitive that the length of both the longest increasing subsequence and the longest decreasing subsequence cannot be small simultaneously. A famous result of Erdős and Szekeres formally justifies this intuition. This is one of the first results in extremal combinatorics, published in the influential 1935 paper of Erdős and Szekeres.

Theorem (Erdős-Szekeres 1935) - A sequence of more than [math]\displaystyle{ mn }[/math] different real numbers must contain either an increasing subsequence of length [math]\displaystyle{ m+1 }[/math], or a decreasing subsequence of length [math]\displaystyle{ n+1 }[/math].

Proof. (due to Seidenberg 1959) Let [math]\displaystyle{ (a_1,a_2,\ldots,a_{N}) }[/math] be the original sequence of [math]\displaystyle{ N\gt mn }[/math] distinct real numbers. Associate each [math]\displaystyle{ a_i }[/math] a pair [math]\displaystyle{ (x_i,y_i) }[/math], defined as:

- [math]\displaystyle{ x_i }[/math]: the length of the longest increasing subsequence ending at [math]\displaystyle{ a_i }[/math];

- [math]\displaystyle{ y_i }[/math]: the length of the longest decreasing subsequence starting at [math]\displaystyle{ a_i }[/math].

A key observation is that [math]\displaystyle{ (x_i,y_i)\neq (x_j,y_j) }[/math] whenever [math]\displaystyle{ i\neq j }[/math]. This is proved as follows:

- Case 1: If [math]\displaystyle{ a_i\lt a_j }[/math], then the longest increasing subsequence ending at [math]\displaystyle{ a_i }[/math] can be extended by adding on [math]\displaystyle{ a_j }[/math], so [math]\displaystyle{ x_i\lt x_j }[/math].

- Case 2: If [math]\displaystyle{ a_i\gt a_j }[/math], then the longest decreasing subsequence starting at [math]\displaystyle{ a_j }[/math] can be preceded by [math]\displaystyle{ a_i }[/math], so [math]\displaystyle{ y_i\gt y_j }[/math].

Now we put [math]\displaystyle{ N }[/math] "pigeons" [math]\displaystyle{ a_1,a_2,\ldots,a_N }[/math] into "pigeonholes" [math]\displaystyle{ \{1,2,\ldots,N\}\times\{1,2,\ldots,N\} }[/math], such that [math]\displaystyle{ a_i }[/math] is put into hole [math]\displaystyle{ (x_i,y_i) }[/math], with at most one pigeon per each hole (since different [math]\displaystyle{ a_i }[/math] has different [math]\displaystyle{ (x_i,y_i) }[/math]).

The number of pigeons is [math]\displaystyle{ N\gt mn }[/math]. Due to pigeonhole principle, there must be a pigeon which is outside the region [math]\displaystyle{ \{1,2,\ldots,m\}\times\{1,2,\ldots,n\} }[/math], which implies that there exists an [math]\displaystyle{ a_i }[/math] with either [math]\displaystyle{ x_i\gt m }[/math] or [math]\displaystyle{ y_i\gt n }[/math]. Due to our definition of [math]\displaystyle{ (x_i,y_i) }[/math], there must be either an increasing subsequence of length [math]\displaystyle{ m+1 }[/math], or a decreasing subsequence of length [math]\displaystyle{ n+1 }[/math].

- [math]\displaystyle{ \square }[/math]

Dirichlet's approximation

Let [math]\displaystyle{ x }[/math] be an irrational number. We now want to approximate [math]\displaystyle{ x }[/math] be a rational number (a fraction).

Since every real interval [math]\displaystyle{ [a,b] }[/math] with [math]\displaystyle{ a\lt b }[/math] contains infinitely many rational numbers, there must exist rational numbers arbitrarily close to [math]\displaystyle{ x }[/math]. The trick is to let the denominator of the fraction sufficiently large.

Suppose however we restrict the rationals we may select to have denominators bounded by [math]\displaystyle{ n }[/math]. How closely we can approximate [math]\displaystyle{ x }[/math] now?

The following important theorem is due to Dirichlet and his Schubfachprinzip ("drawer principle"). The theorem is fundamental in numer theory and real analysis, but the proof is combinatorial.

Theorem (Dirichlet 1879) - Let [math]\displaystyle{ x }[/math] be an irrational number. For any natural number [math]\displaystyle{ n }[/math], there is a rational number [math]\displaystyle{ \frac{p}{q} }[/math] such that [math]\displaystyle{ 1\le q\le n }[/math] and

- [math]\displaystyle{ \left|x-\frac{p}{q}\right|\lt \frac{1}{nq} }[/math].

- Let [math]\displaystyle{ x }[/math] be an irrational number. For any natural number [math]\displaystyle{ n }[/math], there is a rational number [math]\displaystyle{ \frac{p}{q} }[/math] such that [math]\displaystyle{ 1\le q\le n }[/math] and

Proof. Let [math]\displaystyle{ \{x\}=x-\lfloor x\rfloor }[/math] denote the fractional part of the real number [math]\displaystyle{ x }[/math]. It is obvious that [math]\displaystyle{ \{x\}\in[0,1) }[/math] for any real number [math]\displaystyle{ x }[/math].

Consider the [math]\displaystyle{ n+1 }[/math] numbers [math]\displaystyle{ \{kx\} }[/math], [math]\displaystyle{ k=1,2,\ldots,n+1 }[/math]. These [math]\displaystyle{ n+1 }[/math] numbers (pigeons) belong to the following [math]\displaystyle{ n }[/math] intervals (pigeonholes):

- [math]\displaystyle{ \left(0,\frac{1}{n}\right),\left(\frac{1}{n},\frac{2}{n}\right),\ldots,\left(\frac{n-1}{n},1\right) }[/math].

Since [math]\displaystyle{ x }[/math] is irrational, [math]\displaystyle{ \{kx\} }[/math] cannot coincide with any endpoint of the above intervals.

By the pigeonhole principle, there exist [math]\displaystyle{ 1\le a\lt b\le n+1 }[/math], such that [math]\displaystyle{ \{ax\},\{bx\} }[/math] are in the same interval, thus

- [math]\displaystyle{ |\{bx\}-\{ax\}|\lt \frac{1}{n} }[/math].

Therefore,

- [math]\displaystyle{ |(b-a)x-\left(\lfloor bx\rfloor-\lfloor ax\rfloor\right)|\lt \frac{1}{n} }[/math].

Let [math]\displaystyle{ q=b-a }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ p=\lfloor bx\rfloor-\lfloor ax\rfloor }[/math]. We have [math]\displaystyle{ |qx-p|\lt \frac{1}{n} }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ 1\le q\le n }[/math]. Dividing both sides by [math]\displaystyle{ q }[/math], the theorem is proved.

- [math]\displaystyle{ \square }[/math]